In-depth Written Interview

with David Macaulay

Insights Beyond the Movie

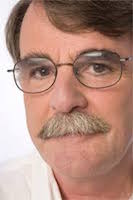

David Macaulay, interviewed in his studio in Rhode Island on August 14, 2001.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Based on your books, you appear to be a rather inquisitive person. Have you always been that way?

DAVID MACAULAY: When I was a kid, I was inquisitive and often went outside and looked for answers. I was an explorer. Grew up in a very small house in the north of England. We all basically lived in one room of this house. It was the family's room. We ate there and did work there and stuff like that. The other rooms were for sleeping and then there was the living room for company, which we never got into. So I spent a lot of time outside, in the woods. That's, I think, where my imagination really began to develop and grow. I was just left to my own devices. It was a wonderful time. I could play in the woods for hours. I could be anybody I wanted to be out in those woods. I didn't have a bicycle. It was just me, running up and down hills in the woods and looking for boroughs and wondering what lived there. The big book for me in those early years was The Wind in the Willows. The Wind in the Willows and life outside were one and the same thing. So, Mole and Toad and so on and so forth were every bit a part of my life as my brother and sister and my parents.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You've chosen an interesting variety of subjects for your non-fiction books. How do you go about selecting what these books will be about?

DAVID MACAULAY: When I sit down to choose a book, I choose a subject. When I choose a subject, I choose a subject that interests me because I know that I'm going to be with it for a long time. I'm going to have to spend a lot of time reading and researching and then, actually working out the book itself. Basically, I'm going to be living with this idea for a year or two or three. So I'd better pick something that I'm really interested in.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Your information books seem to be tributes to design and builders.

DAVID MACAULAY: Yeah, the architecture books are really as much about the building as they are about the people who built the buildings. Now, I didn't get into the personalities because that's a whole different book, but I want you to know that the master planner was sort of making decisions as he decided where the stones should go, where the buttresses should go, where the spires should go, and so on. But, that would depend on the materials at hand. And that would depend on the kind of scaffolding that could be built. And that would ultimately depend on the courage of these people to get to the tops of this scaffolding to hoist these stones into place. We're talking about lifting blocks of stone 150 feet in the air, while standing on, in some cases, pretty flimsy wooden scaffolding. You've got to be driven by something to do that.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Can you talk about Underground?

DAVID MACAULAY: Underground was different from Castle and Cathedral and Pyramid, in that it really is intended as a guide for pedestrians wandering down the city street. So I start with a double page spread of an intersection that we're going to look at in detail. And I put sort of circles around key familiar elements, like the fire hydrant, and a manhole cover, a ladder disappearing into the street, and a construction site excavation. I start with that. And you can move from this map, in a sense, to the corresponding page of the book, or you can just go through the book from beginning to end. Doesn't matter. But it was intended as a guide, a kind of guide for pedestrians.

Underground was a catalog of city sites that are clues to systems we completely take for granted until they break down, and then we say, "Hey, how come I don't have any electricity? What's wrong with the water?" We are so dependent on those systems, and that's what motivated that book. I did the book because I wanted to say to people, "Hey, look again. This is amazing stuff. We all count on it." I mean, I don't know what we'd do without this stuff, but we just completely take it for granted.

TEACHINGBOOKS: City?

DAVID MACAULAY: One of the things about City that interested me from the very beginning is that Roman city planners really thought about the population. True, they may have thought about the population for political reasons, but they thought about the population. How many people can live safely, and in a healthy way, in this limited space? Let's say 50,000, maximum. We decide where the walls go, and we start to fill it. We use a good system because we're going to be building many cities all over the place and we want people to feel at home in each of these cities. So you end up with a good system, you end up with a defining wall, and once that population is reached, that limit is reached, all the systems are working at their maximum, and you start a new city somewhere else.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How about about Unbuilding?

DAVID MACAULAY: To talk about Unbuilding I have to go back to my childhood in England and to the Big Book of Science. The Big Book of Science had a picture in it of the Empire State Building. And before we traveled to the United States, I thought the Empire State Building represented the United States. But the illustration is interesting. The building is really huge on the page, and the rest of Manhattan is this tiny little strip of tall buildings, but small. What the illustrator did was kind of create this fuzzy connection between the big Empire State Building and the small Manhattan skyline. I thought this building was enormous and was convinced we were going to see this building just as we pass Ireland.

Then we lived in New Jersey. And from where we lived in New Jersey you could see the Empire State Building, this faint thing at the end of the railroad tracks. And at night, when it was dark, you would see the light flash. So there was a connection between the Empire State Building and me. I decided I wanted to do another book about a piece of architecture, but I didn't want to do a book about another building from the ground up, like Cathedral or Castle or Pyramid.

So I thought, well, let's take the Empire State Building and have some fun. It's a building I'm obviously connected to. So I thought, well, if somebody was going to buy this building, it will have to be taken apart in exactly the reverse way in which it was built. So it's really about the building of the building, but it's backwards. So for those people who are nervous about seeing such a quintessential American symbol dismantled, all they need to do is read the book backwards.

TEACHINGBOOKS: The Way Things Work is perhaps your most well-known work. Can you share what you were trying to accomplish in this book?

DAVID MACAULAY: The Way Things Work was a challenge that I shunned for a while. When I was initially brought into the process, I said, "No, I don't really want to do this." And then a year later I was asked again and I said, "Okay, let's give it a try." Now, again, like all the other stuff, it was another sort of set of questions that I didn't have the answers to. Fortunately, I was able to work with a team of people, including Neil Ardley, who did have all the answers, and still does have all the answers. So the information gathering was made much easier.

My job primarily with The Way Things Work was to interpret through pictures how things work and what the connections are between the principles behind different kinds of technology. But it was the sheer magnitude of the project that was the most overwhelming thing. It took four years to put that book together.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Can you please share an example of your thought process in selecting and considering an object for The Way Things Work?

DAVID MACAULAY: In some cases I glorify everyday objects because I marvel at the simplicity of them. The corkscrew is an example of this. I mean, here you are talking about something as simple as a screw being driven into a cork. And as it is being driven in, the gears that are attached to it start to raise levers. This is wonderful. And then once that screw has worked its way into the cork, the very nature of the screw means it's not just going to pull out. You're going to have to really yank it. But you've been raising levers the whole time, so that by pressing down on the ends of those levers and pushing down, with very little force, you can actually shift this cork, in spite of the tremendous pressure under which it was forced into the bottle.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Building Big? DAVID MACAULAY: Well, the thing about Building Big that distinguishes it from all the other books is that it was a companion book, and it was intended as such, but it also had to stand on its own. So after doing all the filming of the PBS series, I found myself re-researching this stuff for each of the five subjects and putting together sort of concise chapters that dealt with half a dozen examples to offer another way of seeing the information we had presented on camera.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Can you share an example or two of some of the structures?

DAVID MACAULAY: Yeah. I think one of my favorite examples from Building Big is the Golden Gate Bridge. And one of my favorite things about the Golden Gate Bridge, beyond the fact that it's a spectacular sight is that, in a sense, the basic shape and form of that bridge was designed by nature and other circumstances. First of all, they had to find a place to put the bridge. After going through various locations and looking, they found this ideal spot that was a certain distance at the closest points.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You went up on top of the Golden Gate Bridge, along with other remarkable places for the making of Building Big, did you not?

DAVID MACAULAY: Yeah. One of the great memories of the shoot was being on top of the Golden Gate Bridge. It's about 750 feet high, something like that, and there's a little elevator that takes you up. We went up to film a scene on top. Now, on the bridge, it was foggy and misty and cold, but when we got to the top and opened the trap door and scrambled out onto that deck above the street, it was warm. There was a wonderful breeze. The sun was out. It was really magnificent. And the view, of course, of Marin and San Francisco and the whole bay. You look down on the mist and the fog, and then through it you could see the road with all the cars. And then below that you could see a tanker going by and then, of course, the water, and so on. A real sense of layers of depth. It was an impressive structure, to say the least. The thing about making those films is they present the opportunity of seeing things from unique perspectives. Being on top of the World Trade Center in New York on the window-washing platform, for instance, was interesting.

And it's not always just being on tops of tall things, but just having a chance for me to sort of walk around, kind of behind the scenes – like inside the cast iron dome of the capitol building; that was incredible. It's an erector set. It's a complete fake made to look like stone, but in fact it is cast iron. When you get inside and see how it's pieced together, it's brilliant: a wonderful solution.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You have written a handful of superb fictional picture books, including Black and White for which you won the Caldecott Medal. Can you share your thinking about this picture book?

DAVID MACAULAY: Black and White was an idea for which the earliest sketches, I think, began to appear in the mid-80s. Then that book came out in '91–92. The idea of a journey through a book was something that intrigued me – people taking journeys and meeting and crossing paths and things of that nature. I thought it would be fun to play with because I think of each book as a journey. You know, you turn the pages. You can be in a completely different place and you've just turned a page. Or you can be in a completely different point of view looking at exactly the same thing you just saw in the previous page. There are so many opportunities.

As I did other books, I kept this idea in the back of my head, and kept going back to my sketchbooks, and looking at my sketches. And, eventually, I was able to extract this fairly simple collection of four related stories or one story broken down into four separate fragments, from different points of view – emphasizing the differences by changing the name; giving each its own name; using a different medium for each of the four stories; a different sort of emphasis and focus and a different character. I did everything I could to visually separate each fragment, but, in the end, it's one book. It's one large complex story, like life. I was really pleased with it.

I was incredibly satisfied with the book when I did it, and stunned when I heard from the Caldecott committee that they were going to give it the medal. It never occurred to me that this book was Caldecott material. It was just something that had really been fun. I guess what that means is you should probably concentrate on doing things that really interest you and really get things excited, even if it's taking you years, and not worry about anything else because good things can happen.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Can you talk about Angelo?

DAVID MACAULAY: Angelo is the new book, set back in Rome. I mean, once Rome is in your blood, there is no turning back. This time I decided that I would like to tell a story set in Rome. Rome Antics is a kind of playful tour through the city. Angelo is a story set in a very particular part of Rome. And, once again, we have a pigeon, but this time we have an old man, a plasterer, a restorer, who is working on a façade of an old building. One of the wonderful things about Rome is that it still has so much of its past. And it has so much of its past because people take care of old things. They restore things. They don't just level them and build a new one. I mean, that's what makes European cities different from American cities. And Rome is the epitome of a European city.

So it's a story about someone who is basically giving their life to this restoration process, to keeping things up, to keeping the fabric of the city healthy. But the annoyance has always been, to somebody who works on buildings, is the pigeons who live and roost in all these old buildings and make a terrible mess. So what happens in the story is this man who has to deal with pigeons, his nemesis, suddenly finds himself taking care of a sick bird, a bird that is unable to leave a site he is now going to work on. The story is, of course, about that relationship and about, ultimately, their changing roles in a sense. As he struggles to finish the job, it's the pigeon who, having been brought back from the brink of death by this old man, turns out to be the helper. I mean, the pigeon doesn't learn to plaster, but through a kind of friendship that the old man had not experienced helps him to get through the project.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How did you create the art for Angelo?

DAVID MACAULAY: The art for Angelo is drawn in ink on sort of an archival paper, but a translucent paper. I do that because I do lots and lots of sketches, and when I finally get to the finished sketch, I wanted to trace it, and therefore, rather than set it up on a tracing table, which is a little awkward to work on, I just use a paper that is thin enough so that I can actually trace from my last sketch onto the finished sheet. And then, I'm using pen and ink because the pen is kind of flexible, very flexible, and it creates a line that is somewhat unpredictable. There is a kind of spontaneity to it. Now, you can imagine that if you've made a sketch for a week, trying to perfect the composition and design of a particular drawing, you could destroy the life of the image. But once you pick up this little pen and start to trace it, much of that life sort of comes back because the pen has its own mind, basically. It does what it wants. It drops ink where you don't mean to and so on, to some extent.

And then I apply color. Once the ink is dry I start applying color, and I apply it with markers and in some cases, with crayon over the marker until I get it the way I want. Sometimes I'll go with bleach to pull off the ink or pull off the marker. I have to say with every one of these drawings, once I start playing with color, I'm jumping off a cliff. I have no idea how it's going to work out. I always know, from the beginning, that the worst thing that can happen is I have to draw the whole thing again. That's the worst thing that can happen. That's not so bad. But I prefer that I can just draw it once.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Do you use that same medium for all your books?

DAVID MACAULAY: I used markers for Ship. I used markers for Building Big. For The Way Things Work I used watercolor and gouache on heavy opaque white paper. A lot of it has to do with the speed at which you want to work. Angelo was being drawn fairly quickly. Building Big had to be drawn fairly quickly because of deadlines. And, in that sense, the art won't last as long. The physical art that I make doesn't have the kind of archival quality that, let's say, the stuff from The Way Things Work does.

The art is the finished book. All the stuff I have to make to get to the finished book I make it as well as I can. But when all is said and done, those things go back in a drawer some place. They're what is left over. When I hold the book and turn the pages, that's when I know whether or not I've succeeded, and that's what matters.

[Editor's Note: The next two questions were added after the original interview.]

TEACHINGBOOKS: What inspired you to write Mosque?

DAVID MACAULAY: I was inspired primarily by the buildings themselves, particularly the work of the great Ottoman architect Sinan. His buildings in and around Istanbul are wonderful structures, beautifully designed and exquisitely constructed. In my history of western architecture class back in college, I had been introduced to Hagia Sophia, the famous Byzantine basilica that eventually became a mosque, but I knew almost nothing about all the other buildings in Istanbul that were actually built as mosques. I didn't begin to appreciate them until we began filming the dome episode of the PBS series Building Big.

I first considered creating a book about the building of a mosque when I was doing the architecture books back in the seventies, but I just ran out of steam on the series and wanted to try something else. Twenty-five years later September 11 happened.

I've always tried to make books I thought would be useful. This time I wanted to make one I thought might actually be needed. Not so much because it would explain the differences between people, but rather because it might remind us of the similarities. Great architecture seems to bring out the best in people, not only in those who create it but also in those who use it and are moved by it. It doesn't' matter where in the world we encounter the finest buildings. They often have a universal appeal, an emotional as well as an intellectual one that goes way beyond their inherent respect for gravity.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you hope people will understand and remember most after reading Mosque?

DAVID MACAULAY: Beyond the idea that all people when challenged and inspired seem capable of remarkable achievement, I want my readers to remember that in most cases the mosque is the religious centerpiece of a complex of buildings, each created to house a specifically religious as well as socially motivead activity, whether a school, soup kitchen, hospital, etc.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You're trained as an architect. How does that affect your career as an illustrator?

DAVID MACAULAY: I was never supposed to be an illustrator. I studied architecture, and I knew close to the end of my architectural training that I did not want to be an architect, but the great thing about architecture is it teaches you how to solve complex problems. It shows you how to break problems down into manageable pieces and then put them back together to create a building or a city. I have found that way of looking at things particularly useful for explaining how things work, but also for piecing together a book. There's a logic to piecing together a book.

I would recommend that people study architecture, even those who want to go into politics, who want to go into medicine, who want to go into just about anything because it's a wonderful way of fooling yourself into believing that you can solve any problem that is thrown at you.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You teach illustration at the Rhode Island School of Design. What do you talk about with your students?

DAVID MACAULAY: I teach illustration. Very specifically dealing with sort of convoluted weird problems that I want my students to interpret visually. I want them to know that when they make a decision on a piece of paper, there has to be a reason for that decision. If they don't think about every aspect of the image they make, they're missing opportunities. They may be misleading the person who is looking at the picture, inadvertently, putting something on the left-hand side rather than the right-hand side. I mean, it changes the way we look at things, putting something on the top or the bottom. The way our eye moves around this map that we call illustration is critical, if we are trying to convey a particular journey. If it's just, "oh, look at it and see what you feel," that's something else again. But an illustrator has a real job to do, and you must understand the job that has to be done, and then you must understand how to manipulate the surface so that the information is successfully conveyed. That's the challenge to me. That's what I love.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Are you all about visual interpretation?

DAVID MACAULAY: I'm not so sure I'm about visual interpretation as much as visual explanation. I think much more in a kind of nuts and bolts way in my illustrations, even in my illustrations about the relationship between an old man and a pigeon, I'm thinking about the nuts and bolts. I'm thinking his head is too big. This pigeon has suddenly grown three years in just one turn of the page. I'm always aware of the technical stuff, but I'm also, from a compositional point of view, trying to get you to feel something about the story as well. I mean, that's got to be part of it. Just making anatomically correct drawings of characters in a book is nothing.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How has your work evolved over the years?

DAVID MACAULAY: I think that because I've been doing this now for almost thirty years there's a certain confidence in the books I do and in the drawings I make that wasn't there from the beginning. I'm also willing to take chances because I'm given the opportunity to take chances with things. I could have done more building books. I could have done forty books each about the building of a different structure. Now I'd be at the bottom of the list, carport and family room, but it didn't interest me. What interested me was, "Okay, I know I can do this. I love this process of making books. Where can I take it? What can I do next?" So, you find yourself moving into a Motel of the Mysteries or whatever. But it's partly because you're given the opportunity by a publisher who says, "You know, we like the way you think. You have interesting ideas. We want to see you do more." That kind of encouragement makes all the difference. It's essential.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What's next? DAVID MACAULAY: Well, what's next are two books, actually. I'm about to start two projects, one on the human body and one on the fossil. I've been doing research on both of these things, on and off, over the past few years, but now it's time. And that's usually what happens with these books. You don't just think, okay, it's January first, what will be this year's book? You think back what ideas are intriguing. Look at those sketchbooks. Sometimes I'll just look at the sketchbooks and see what ideas never went anywhere and try to figure out why. But these two ideas have been cooking for quite a long time.

The human anatomy, human engineering, how a body works is something that I think could be very useful. I'd love to produce a book that made the body really accessible to people. Not filled with medical stuff. Not filled with medical looking drawings. Filled with exciting drawings that made you think, "Wow, that's a fantastic thing. That's what a knee is. Or a hand, you know, that's how that finger sort of bends and straightens and bends and straightens." Those things, those are the questions that really appeal to me, and I think that they can be answered in a very exciting way. There's a level of knowledge of human anatomy that I won't even attempt to go after, but if I could just make the engineering of the body as exciting as I happen to think it is, then that would be a contribution I'd be happy to make.

The fossil is really a story of time. I have a crab fossil that was found on the Great Pyramid in Egypt. How did it get to the top of the Great Pyramid is the question. That's the big question. Underneath that question are a million other questions that take us back forty million years to moving continents and disappearing oceans and all kinds of stuff. So that is the other book that I'll start working on. And I'll probably do these simultaneously.

This In-depth Written Interview was created by TeachingBooks.net for educational purposes and may be copied and distributed solely for these purposes for no charge as long as the copyright information remains on all copies.

Questions regarding this program should be directed to info@teachingbooks.net