In-depth Written Interview

with Brian Selznick

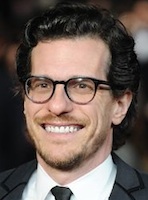

Brian Selznick, interviewed in his home in San Diego, California, on March 13,2009.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Until you won the 2008 Caldecott medal for The Invention of Hugo Cabret—a 544-page, middle-grade novel containing nearly 300 full-bleed pencildrawings, you were known widely for your beautifully illustrated picture book biographies.Where did Hugo originate?

BRIAN SELZNICK: I had seen A Trip to the Moon by Georges Méliés many years ago,and I had wanted to do a story about a kid who meets Méliés, the way that Victor metHoudini in my very first book, The Houdini Box. But I didn't have a plot and I didn't have a kid character. All I had was the idea of a kid meeting Méliés. That premise sat in my headfor 15–18 years; a really long time.

TEACHINGBOOKS: After all that time, how did Hugo materialize at last?

BRIAN SELZNICK: There was a period of about six months when I was really wiped out, and I didn't want to do anymore picture book biographies. But, those were the only booksthat were being offered to me. I kind of shut down for a while, and I didn't work for about six months, and it was a very depressing time. I didn't know what I was going to do. Hugogrew out of that period.

It's funny to go back to that time, because obviously everything has turned outreally well with Hugo. But before Hugo existed, I had no way of imagining that anything like Hugo would ever happen. In retrospect, it's easy to say it was a really hard time, butduring the six months, it was really devastating, and I really felt at loose ends.

When I got the idea for Hugo, it sort of was out of an act of desperation. I thought, "Well I don't have anything else to do, so I might as well work on this vaguely impossible project."

TEACHINGBOOKS: What sorts of things did you do to draw out his character and story?

BRIAN SELZNICK: I did a lot of reading. I pulled things off of my shelves and went tobookstores and bought random books that looked interesting. One of the books Ihappened to read was called Edison's Eve by Gaby Wood. It's about the history ofautomatons, and there was a chapter about Georges Méliés. It turned out he actuallyowned a collection of automatons that were donated to this museum at the end of his life, and then they were all destroyed.

As soon as I read that, I had this vision of this kid climbing into the garbage andfinding one of those broken automatons and trying to fix it. I didn't know anything else. I didn't know who the kid was. I didn't know why he was going through the garbage, but Iknew it was the beginning of a story. I started writing things down; doing more researchabout Méliés and automatons.

But there were a lot of problems with the idea. No kid would know who GeorgesMéliés was. Kids don't watch silent movies. Would kids be interested a story that took place in France in the 1930s? But I didn't have any other ideas. So, I just kept working onit, and it caught my fancy. I got interested in this kid and what he was doing and why hewas interested in these machines, and I started talking about it with friends who arewriters, and passing ideas back and forth with them.

We asked, "Why would the kid be interested in machines? Maybe his father workswith machines. Maybe his father's a clockmaker ... Maybe Hugo has a real talent for working with machines and he can fix them." I asked all these questions, and then theanswers became the plot of what eventually was the book. I just kept working on it.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What about the groundbreaking format of Hugo Cabret? How did that evolve?

BRIAN SELZNICK: That came much later. It started off just as an idea for a novel. WhenI finally did present it to Scholastic, I said, "I have an idea for a novel." I knew from thebeginning I wanted to do something different or unusual with the pictures, but my sensewas it was going to be one drawing per chapter, like a traditional illustrated novel. But Iwanted to do something different with that, like maybe somehow that one drawing in eachchapter would be important in some way, but I had no ideas. I talked to Scholastic aboutit as a regular novel—my original contract for the book was for a 100-, 150-page novelwith one drawing per chapter.

I proceeded to work on the plot of the book, mechanically trying to figure out whatwas going to happen next. I asked myself, "If this happens, what do I need to havehappen here, and if I need to get to this point in the story, what has to happen in thebeginning?" I had written three other books at that point, but they were all much shorter and much more simple. I had never written anything with so many characters and somany plot turns, and I just didn't know what I was doing.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How did you figure things out?

BRIAN SELZNICK: I started watching a lot of French silent movies as research. Beforethis, I had seen the Méliés film but almost nothing else. I didn't know anything about thehistory of French cinema. I started watching all these movies. The book was going to takeplace in 1931, and I started learning about the transition from silent movies to sound thatstarted in 1927 with The Jazz Singer.

>Then, I started thinking about how, after sound was brought in, some of the earlyfilmmakers used it in these unusual ways. They didn't just suddenly turn on a microphoneand start making movies that had start-to-finish sound. Some of them would use sound in these very experimental, interesting ways that helped comment on the story. Thatintrigued me.

Then I thought, "Maybe I could do something like that with the pictures, where thepictures actually help tell part of the story." I guess that was the beginning of the idea. Ithought about picture books. I thought about Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak. I thought about Fortunately by Remy Charlip, where every time you turn thepage the story advances. It goes from a happy page to a sad page. It goes from black and-white to color.

I made connections between that and the cinema, because there are so manydevices that are used in the picture books that echo filmic devices, like editing andpanning and close-ups and the way time is used. There are echoes between illustratedbooks and film. So I just kind of put all that together.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Please describe your process of turning Hugo the novel into what it is today.

BRIAN SELZNICK: I thought, "Well, what if I tell part of the story with pictures?" Ibasically just went back and took out all of the text that I could and replaced them withwhat I wanted the picture sequences to be. I knew I didn't want to do word bubbles like a cartoon, so it had to be purely visual if it was going to exist as a picture in the story.Anything where a character was thinking about something, anything where a character was talking, anything where a description gave you insight into something because of thelanguage I used, it had to stay as language. But if I was describing action—if I wasdescribing something that was happening or something that the characters were lookingat—I took out my descriptions and replaced them with lists.

If you were to read through early drafts of my manuscript, you'd be reading the text and then there'd be a list, and it would say, "One, we see Hugo walking down the street.Two, we see that Hugo is following the old man. Three, we see them turn the corner.Four, we see a close-up of Hugo looking over his shoulder. Five, we see ..." And so that's how it existed for a long time.

I knew that I wanted every drawing to be a double-page spread, so that everyimage required a page turn. But that meant that taking out one written line, such as,"Hugo followed the old man home," and replacing it with six drawings where we followHugo through the streets of Paris, which became 12 pages in the book. So suddenly, ithad exploded into a book that had gone from 100 pages to possibly being 600 pages,which was not what Scholastic had signed up for.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What happened next?

BRIAN SELZNICK: I had to call Scholastic and explain this idea, and amazingly, from thevery beginning, Scholastic said, "Yes, we love it, keep going, take out more words, makeit bigger, we'll find thicker paper." They loved the idea and they thought it would work.That was very heartening for me, although I still didn't know if kids would like it. It's great to have your publisher behind you and on your side. I appreciated that more than anything. By the time I finished Hugo, I did actually feel like it was good, and I did feel like the story worked. But, that didn't mean that I thought kids would like it.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What were your concerns?

BRIAN SELZNICK: When I was working on it, someone had said to me, "You're workingon a book about French silent movies for kids? That sounds like a terrible idea." I guesstechnically, it is a terrible idea. But my editor said that if these elements—like Frenchsilent movies—are important to your main character then they will be important to your reader.

I felt like I had done what I wanted to do with it, and that was very satisfying. Ithought to myself, "Okay, even if kids don't read the book and don't like it, I have learned a ton of stuff making this book, and so I'll just apply what I've learned to the next thing I make."

It wasn't until I went on tour and I met the first group of kids on the very first day of my tour, where the kids had read the book before I got there, and they were clutching it totheir chest, and the teachers told me all these great things about the kids' reactions when they read the book. The kids were telling me their experiences, too, and that was the firstindication I had that kids might actually like the story.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What kind of feedback about The Invention of Hugo Cabret have you received from students?

BRIAN SELZNICK: I can't tell you the number of times I have heard stories about kidsasking to see silent movies after reading the book. I have heard about, and participatedin, many little film festivals for kids inspired by Hugo, where they show silent movies andother movies that I watched when I was working on the book, because kids got excitedabout it, because they're given a context.

The Invention of Hugo Cabret gives students a framework through which tounderstand silent movies. Without context, the movies are sort of weird things with nosound and no talking and the film is jumpy. Kids don't automatically know how to relate to them. But, after having read Hugo, they understand why silent movies are interesting.They get what Méliés was doing; the book gives them a way of stepping into that a littlebit.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What was it like winning the Caldecott Medal for this project ofwhich you were so unsure?

BRIAN SELZNICK: It was really shocking. I guess I still don't know quite how to frame itor how to think about it. It was an amazing thing. Before the announcement of theawards, there was a lot of talk about whether or not Hugo was even eligible for theCaldecott or the Newbery. The whole goal of making a successful children's book is locking the words and the pictures together so that they're inseparable, and then the two major awards for children's books ask you to completely separate the words from thepictures in determining their merits.

So, it was a matter of whether or not the ALA committee would be able to define the criteria to fit Hugo's format. There was just no way of knowing how things would beidentified. Many people were saying to me how sad it was that my book was going to bedisqualified because it couldn't win either award.

By the time the awards were announced, I was in a very lucky position, in that Hugo had found an audience by that point. Kids were reading the book, teachers andlibrarians were sharing it with the kids—it was being read.

I thought, "Okay, well even if it doesn't win, it's found its audience, which is the point of what we do." We authors and illustrators sit all day hunched over our desksworried about what we're making, because we want the audience to read it and we wantour audience to like it. Then the phone rings and you're given this incredible acknowledgment.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Please share the "phone call" moment.

BRIAN SELZNICK: That morning, I was in California. The phone rang at 3:30 in themorning with the ALA committee on the phone, headed by Karen Breen, the chair. Thephone rang and I knew why, so I jumped up. My boyfriend was telling me, "Get thephone! Get the phone!" I said, "I'm trying to get the phone!"

I finally hung up the phone, crying. My boyfriend saw the whole process of Hugo. He saw how difficult it was. He dealt with me yelling at him because he would say thewrong thing to me. He would tell me that he thought something was good when Iobviously knew it was terrible, or he would be afraid of saying anything, and then I wouldyell at him for not telling me it was good when I was in need of a positive feedback. Hesaw the whole process. So, the first thing he said to me after I hung up the phone and wesat down and just sort of tried to take it in, he turned to me and said, "Now, do you think it's a good book?"

It was amazing, you know. It was an incredible step in this progression ofacceptance where knowing that the kids were reading the book and liking it. It was anincredibly important thing. Then getting this acknowledgment from the CaldecottCommittee, I can honestly say it was something I literally never imagined. I had gottenthe Caldecott Honor for The Dinosaurs of Waterhouse Hawkins, and that's incredible and something beyond which you can't even hope for. You just can't hope for stuff like that.

I actually remember working at Eeyore's Books for Children in Manhattan when the ALA award announcements would be made. We would get rolls of the stickers to putthem on the copies of the award-winning books that we had in the store. I remember specifically thinking that the work I did would never be looked at by the people who giveout these awards. That was just an entirely separate class and category of work that Icould never aspire to. I could aspire to being as good as I could be in making the books Iwanted to make, but ... I actually stole a roll of Caldecott stickers when I stopped workingat Eeyore's. Those gold stickers are beautiful, and I wanted some. I still have them in mycloset. So now, to go into a bookstore or a school and see kids holding my book with thatgold sticker on it—it's a really spectacular feeling.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How did you get started in children's books?

BRIAN SELZNICK: For me, everything really started at Eeyore's. I feel like my entire education in children's literature took place at that store. I got the job there sort of bycharming my way in, because they were looking for someone who had an extensiveknowledge of children's literature, which I believe is what the "Help Wanted" sign in thewindow said, and I didn't know anything about children's literature at the time.

My goal for getting the job was to learn about children's literature. So Steve Geck, who was the manager, basically turned me away and said, "Thanks, but you don't know anything." I told him that I'd really love to learn. He sent me away, and told me to go studyand to come back. I did. I went to other bookstores. I went to the library. I tried tomemorize names of books and found a few other things that I thought would beimpressive.

I came back without much more knowledge of children's literature, but I think Steve was just impressed that I actually came back. I was really excited to get the job atEeyore's. It was one of the oldest children's bookstores in the country.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What was your education at Eeyore's Books for Children like?

BRIAN SELZNICK: Steve knew everything about children's literature. He had grown up at a children's bookstore. His parents owned the Tree House in Minnesota. He took meunder his wing, and sent me home every day with bags of books to read. He'd just tick offhis favorite picture books and novels and nonfiction books, and I started reading as muchas I could. A lot of the other staff also had been there for a while and knew all about books. I was so impressed when a customer would come in and vaguely describe an ideaof a book or memory of what a book cover looked like, and my coworkers would be ableto find the books based on those little hints.

Then just reading all of the books and meeting all of the customers at the storereally taught me about what children's literature can do, what the possibilities were. Iremember especially rediscovering the work of Maurice Sendak, especially Where The Wild Things Are, and then finding Richard Egielski and Arthur Yorinks's collaborations, like Oh, Brother and It Happened in Pinsk and Louis the Fish.

Those were especially exciting to me in terms of how a story could be toldbecause Richard's illustrations for these stories often started before the text of the storydid. They started either on the endpaper or on the title page, and the illustrations finishedthe text in really smart and comprehensive ways, so that the story was not fullyunderstood without both reading the text and looking at the pictures. I found that veryvaluable in terms of what a picture book was when it was time for me to start trying tomake my first book.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What was the turning point that started you on your book career?

BRIAN SELZNICK: There were great story times and all sorts of things like that. Ieventually told Steve that I was also an artist and was thinking about doing books eventually. I think he asked me if I wanted to do a window display, or maybe it was myidea, I can't remember, but Anthony Browne, the illustrator and writer of the book Gorilla and many other great books, was coming to town. I was allowed to do the windowdisplay.

I went looking for a huge piece of paper to paint a gorilla on to hang in the window,and I couldn't find any piece of paper big enough. I got the idea to just paint it directly onthe glass. I painted the gorilla backwards, from inside the store on the glass, so it lookedgood from out in the street, but it also looked good from the inside of the store. Thatbecame the first of many, many windows that I did at Eeyore's. I painted them for the nextseveral years when I worked at the store and they became known on the Upper WestSide of New York where the store was located.

I did author appearances, holidays, different themes, different big book releases,and those windows ended up becoming a very good education for me in what book covers are supposed to do. Book covers are supposed to catch your eye from across thestore. They're supposed to bring you to the book, to cause you to open the book andwant to read it. A store window display has a very similar thing, where you're supposed tosee the window from across the street, be drawn into the store, see it up close. Thatbecame very useful for me.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Were you always interested in art as a career?

BRIAN SELZNICK: Yeah. I grew up in suburban New Jersey, in a town called EastBrunswick, which had a very good art program in the public schools, of which I took greatadvantage. In high school, there was an arts journal that I edited and for which I did a lotof illustrations. I did some pictures for the yearbook; I used to design T-shirts. The highschool football players asked me to paint skulls and flames on their football helmets. Iwas sort of known as the kid who could paint. And, I had the first one-man show atChurchill Junior High School when I was in ninth grade.

I also liked to build sets at a very young age. There was a little patch of woodsbehind my house, and I played at the edge of this little patch of woods for a long time. Imade a GI Joe island where I built stick architecture: huts and bridges and roads. I alsoused to make little areas for my troll doll to hang out.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Have set design and artwork have always been intertwined for you?

BRIAN SELZNICK: I feel like every book I've done has been influenced by the fact that Ilove the theater and was a set designer first. I became an illustration major at the RhodeIsland School of Design [RISD] where I took painting, figure drawing classes and someconceptual classes. I also pursued a degree in theater design at Brown University: setdesign, costume design, acting ... It seemed perfect for me.

In a conceptual art class we had an assignment to "do something about Houdini," and we had a week in which to turn in the assignment. Other people did paintings andsculptures, but I ended up making this little folding glass, accordion-like structure that hada different part of the picture painted on each of the pieces of glass, so that when youlooked through all of the pieces of glass lined up, it made this three-dimensional picture of Houdini on stage performing one of his tricks. On the back of each of the glass panels, Iwrote a little story about a kid who gets to meet Houdini, because that's what I would have wanted when I was young. Houdini was one of my heroes. Ultimately, that collegeart project became the inspiration for my first book: The Houdini Box.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How did you turn your Houdini college art project into a children's book?

BRIAN SELZNICK: After I got the job at Eeyore's, and I felt ready to start working on myown book, I started reading that story to kids. I had some friends who were teaching, andI would go their classes and I would read the story to them just printed out. I didn't have any drawings, so it was just the text. I had rewritten the story a lot from the time it was theshorter version for the college project, and it was very enlightening to read it to children.

I found there were certain places in the story where I was pausing to builddramatic effect. So when it was time to make the page layout for the book and make thedummy, where you have a miniature version of the book where you can flip through andsee how the pages are turning, I built those pauses from my storytelling into the pageturn, so that the reader has to pause to turn the page in the same places I was pausing tobuild dramatic effect.

The reading of it went into the building of the structure for the book, and the book came out while I was still working at Eeyore's. So that was really fun to be a bookseller with my own book for sale at the store. I would hand-sell it to a lot of customers, and I gotto do a window for it. I basically put into that book everything I had been learning aboutchildren's books from Eeyore's—everything I had studied from Richard Egielski and Where the Wild Things Are.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What's an example of something that's a reference to Where the Wild Things Are in your book The Houdini Box?

BRIAN SELZNICK: The structure of the way Sendak illustrates Where the Wild Things Are was very influential on my creation of The Houdini Box. In the beginning of Where the Wild Things Are, we have a small illustration in a little box in a big sea of white space,and the text says, "The night Max made mischief of one kind and another ..."

Then you turn the page, and it's another little box, perhaps a little bit bigger, andas you continue to turn the page and Max gets sent to his room, the pictures grow andgrow and grow, until we come to the wild rumpus and the wild thing at the place wherethe wild things are, and the pictures have literally taken over the book. There's no more white space. It's a full-page bleed all the way around. When Max returns home and isback in his room. His room itself has grown and it takes up over half the book.

So just with the way Sendak structures the layout of the pictures, we come tounderstand that Max's life has changed. His view of his home when he returns home hassomehow been affected by the adventure that he goes on. It's not overtly stated by Sendak and probably it's not anything that a reader would specifically notice, but it's something that we understand, as the story is progressing.

For The Houdini Box, I wanted the book to feel very much like an old-fashionedblack-and-white photo album. I was thinking about how Sendak used the growing picturesto help underline the emotional journey that Max goes on. So, I started The Houdini Box with the curtains opening. We see Houdini on stage, and all of the drawings for The Houdini Box start off on the left side of the page. You open up the book, and the drawingis on the right side and the text is on the left side. Traditionally in a book like this, thepicture would be on the left side and the words would be on the right, but I reversed itbecause I wanted you to see the picture of Houdini first on the right side, and then moveyour eye over to read about him.

The pictures all remain on the right side. We turn the page. We see a picture ofVictor, the 10-year-old protagonist in the story, who's standing in the same position Houdini is. So all the pictures are on the right side of the book, until Victor's mother takes him to the train station. There, he coincidentally meets Houdini, and when he does, weturn the page, and for the first time, the illustrations have switched sides. So now thepictures are on the left side.

Again, it's not something I would want the audience to notice specifically, but it'sa way of underlining that something has shifted, something has changed for Victor by theway I place the drawings in the book.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Can you share some other specifics of how you reference thetheater in your book illustrations?

BRIAN SELZNICK: Many of my books have some form of curtains that open up. The Houdini Box starts with a closed set of curtains that open to reveal Houdini standing on stage. The Dinosaurs of Waterhouse Hawkins opens with Waterhouse pulling aside a red velvet curtain. When Marian Sang starts on stage.

The Invention of Hugo Cabret has a lot of elements that are connected to the cinema, but elements of the cinema are also connected back to the theater: the idea of sitting in a room that's darkened and then the curtains open, and a group of people sharethis experience together watching something unfold in front of them. Again and again, itsort of goes back to what was exciting to me about the theater.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Let's look back at your picture book biographies, created primarilywith author Pam Muñoz Ryan, including Riding Freedom and Amelia and Eleanor Go for a Ride.

BRIAN SELZNICK: When I was offered the chance to illustrate Riding Freedom, I gotreally excited about it. I was amazed to learn about Charlotte Parkhurst, who lived her lifedisguised as a man, and I loved how author Pam Muñoz Ryan embroidered on the fewfacts we know about her. In Riding Freedom, I illustrated one drawing per chapter.

When I learned that Pam had written a book about Amelia Earhart and Eleanor Roosevelt, I remember thinking that I really wanted to illustrate that book. I feel like thatbook was a big turning point in the work I was doing. Things just came together withAmelia and Eleanor Go for a Ride. It was unlike anything I had done before. The editor gave me one of the best pieces of editorial advice for a specific project that I had ever had. She basically handed me the key to the entire project, saying, "I picture this book like a 1930s movie musical," which was really the right thing to say to me. That becamethe language of the book.

I re-watched a bunch of movies from the ʻ30s. I saw some I'd never seen before, like Flying Down to Rio with Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. There's some imagery in the book that's taken directly from that movie. The black-and-white quality of the book istaken from 1930s glamour photographs. I used black, white, and purple because thosephotographs had a richness to them that I felt I needed one other color to capture. Thewhole aesthetic of the time period is really beautiful. I researched art deco and looked atmovie posters. The research opened up a whole new way of thinking about building abook and telling a story.

I opened Amelia and Eleanor like the title sequence in Flying Down to Rio where we see a little airplane in the distance and it comes toward you, and out of the propeller spins the title. I use page turns to help tell the story and make visual connections that aretied into the way I draw the pictures.

For instance, in one page we see Eleanor Roosevelt getting ready in her room,and she's pulling on one of her white gloves. Then we turn the page, and we see AmeliaEarhart getting ready for the evening, and she's actually in the exact same position that Eleanor is, except mirrored, and she's also pulling on her glove. That use of mirroring, sothat visually we have a connection between two images that is not necessarilycommented on anywhere else. Pam is talking about how these two women are birds of afeather and their friendship, and so it's a way of making us understand that in a visual way.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Then you illustrated another biography by Pam Muñoz Ryan: When Marian Sang.

BRIAN SELZNICK: Yes. Pam and I really wanted to work together again, and when I was working on Amelia and Eleanor, my uncle told me that he had met Eleanor Roosevelt. In my research, I found a photograph of Eleanor Roosevelt standing next toMarian Anderson, and my uncle told me he had met her as well.

I told Pam about this and Pam got the idea to write this story about MarianAnderson. So the way that Amelia and Eleanor was structured as a movie, it made sense to structure Marian as an opera. It became the staging of the opera of her life. So I got todo all this really fun research at the Metropolitan Opera archives where I went down intothese very dark, low-ceilinged hallways and got taken back to archives. I got to gothrough old photographs of what the original Metropolitan Opera looked like before it wastorn down to make way for Lincoln Center and to look at the productions that MarianAnderson was in. I was looking at the way the stages were designed. I even went toPhiladelphia and met people who knew Marian Anderson.

The whole process was really amazing. For that, I also thought a bit about theWizard of Oz, which I think has one of the greatest moments in cinema history, which isthe moment when we go from Dorothy's black-and-white world in Kansas, and she opensthe door into the Technicolor world of Oz. I always think about that moment and howincredible that is, and how beautifully it uses cinema.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How did you apply this idea to When Marian Sang?

BRIAN SELZNICK: I knew I wanted the Marian Anderson book to be in sepia tones, tohave this very rich, old-fashioned feeling to it. But I also wanted to use some moments of color—like in the Wizard of Oz—to make certain moments more important. If the Wizard of Oz had opened in color, when Dorothy got to Oz, it wouldn't have been thrilling at allfor her to open the door. But because the film begins begins in black-and-white, whenshe opens the door, everything is different, and it brings more drama and meaning to the moment.

>There's a perfect analogy there between opening a door and turning a page—everything is different, which is what a good page turn should do. Remy Charlip, anillustrator whom I also really adore, wrote an essay about page turns called The Page is a Door. In When Marian Sang, when she first goes to the opera, you turn the page and we see Madame Butterfly, the opera that she sees, and it's in color. It's just a way of markingan emotional experience, a moment of difference. So at the end, when Marian herselffinally is on stage at the Metropolitan Opera, it also is in full color.

TEACHINGBOOKS: The Dinosaurs of Waterhouse Hawkins continued your well-established tradition of incredibly researched/detailed picture book biographies.

BRIAN SELZNICK: That book was a big production. As with all my books, it started witha great story. My editor told me the story of a guy who built the first life-sized skeletons ofdinosaurs. She sent me the manuscript by Barbara Kerley, and I found the story to bereally amazing.

The manuscript ended with a dinner that Waterhouse had inside the model of oneof his dinosaurs for all the famous scientists of the day. That was triumphant. That wasthe end, and then there was a little author's note. It basically said, "Oh, by the way, healso came to New York several years later to build dinosaurs in Central Park, but he gotin trouble with Boss Tweed, and all of his dinosaurs were destroyed and buriedsomewhere in Central Park, where they still remain to this day."

I called up my editor and said, "The story's good, but the author's note is incredible." I said that really has to be in the book; that's what I want to draw. So she called Barbara, and it turned out that Barbara originally ended it like that, with the piecesbeing buried in Central Park. But another editor had told her that was too upsetting for children, and she should end the story on a happy note. Now, Barbara was able torestore the manuscript to the way she had originally intended it.

I got to go to London to go see Waterhouse's dinosaurs for myself, because thedinosaurs that he built in London are still standing. When I was there, they were in a bit ofdisrepair, but they've been fixed up since. I got permission to go onto the island with thedinosaurs, which the public is generally not allowed to do. They're meant to be seen across a little body of water on an island—sort of like you're at a zoo. I was there for three days climbing in and photographing the dinosaurs. For me, it's that experience of beingsomewhere—of touching something, of feeling it—that gives me a certain sense ofpermission to move forward with the illustrations.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Please explain what you mean by "permission" to move forward with the illustrations.

BRIAN SELZNICK: I'll get a lot of ideas about how I want to illustrate something or what Iwant the drawings to be. But until I feel like I actually know something about the subject—until I've really read about it, until I've really talked to people who are experts on the subject, until I've traveled to the place (if possible) where the story takes place and beenthere and experienced it—I don't feel like I have the right to make the pictures. I have to earn that right.

For me, going to the island, meeting people there, and talking to experts onWaterhouse Hawkins gave me that sense of permission. When I came back to New York and sat at my desk doing my pictures, I knew I'd been there.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What does that permission help you to do with your illustrations?

BRIAN SELZNICK: When you're illustrating, even if it's a nonfiction book, things get changed. You've got to move something slightly to the left or there's some part of that picture that's unknown, so you have to make it up. I feel like I have to know as much aspossible, so that if something either does have to change or if something does have to bemade up, I can do that with some sense of authority.

So the dinosaur book definitely built on what I had learned while I was doingAmelia and Eleanor Go for a Ride, and because that came between Amelia and Marian. When I did Amelia, I felt like there had been a jump in the quality of my illustrations.

When I did Waterhouse, I used things that I learned while illustrating Amelia and Eleanor. You'll see the technique of mirroring an image to make a connection betweenpages, and other ways of telling the story, but I definitely felt like I had grown and waspainting in a way I hadn't painted before. I definitely felt like I was learning something as Iwas working on each new book.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Many people may not associate Frindle and Andrew Clements's other books with you; similarly with the Doll People books. However, both are certainlypart of who you are.

BRIAN SELZNICK: Frindle by Andrew Clements was given to me to illustrate, and it wasone of those times where you read a manuscript and you just cry. I loved the story; itactually made me cry. After reading the manuscript, I wanted to be part of the life of thatbook. Once we came up with the idea of having the kid on the cover holding somethingforward—he's pushing that pen forward—once we got that idea, the publisher liked it alot. So as Andrew wrote other books we kept trying to keep that image. I love that it's become this sort of identifiable look for many Clements books. He writes on subjects thatare serious and real, and often not covered elsewhere. I think that he's a really good writer, and I'm really proud to be part of that ongoing series of books.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Now about the collaboration for Doll People. Those illustrations are quite extraordinary; they're richer and richer every time.

BRIAN SELZNICK: The Doll People collaboration with Ann Martin and Laura Godwin is very, very fun—but managing to make all of those little illustrations fit in the appropriatepoints in the text is a challenge.

When I got the first book to illustrate, I had the idea to do it sort of like a classic book like Winnie the Pooh or Charlotte's Web, where there are little spot illustrations throughout the book. Many chapter books have one drawing per chapter, but another traditional way of illustrating a chapter book is with little spot illustrations that runthroughout the text. I thought, "What if I did that, but did it really profusely so that therewas a drawing on almost every other page?"

I designed and built all of the dolls. I sewed their little outfits, and I made them outof clay and wire and rubber so that I can bend them into all the different positions. I madelittle models of the dollhouses and did a lot of research about old-fashioned dolls and modern dolls.

I did my little sketches about where I wanted the drawings to go, and then thedesigner and I sat down together and tried to make all of the drawings fit. But if a drawingis a certain size, there are only so many words that are going to fit on that page. If thewords that are describing that drawing get pushed to the next page, it won't make sense. So, it's a big puzzle.

So we did the first book, and then Ann and Laura had an idea for the second book, The Meanest Doll in the World. That one was way before Hugo, but I was already startingto think about how else I could illustrate a chapter book. I wanted to see if I could startexperimenting with some of the ideas about page turns. The only real place to tell anarrative in a fully written novel, I thought, would be in the beginning before the storystarts, because everything else is actually told in words. Novel writers aren't going to let you take out giant chunks of their text.

That's what gave me the idea to do the illustrated opening for The Meanest Doll in the World, where you turn the pages and the title scrolls across each page one word at atime, and then the little mean doll, who's the title character, Mean Mimi, picks up a littledoll pencil and scribbles all over your copy of the book. The title page in the publishedbook actually has her scribbles on it. I've heard stories of people returning their book tothe bookstore because they think someone has drawn inside the book. The bookseller has to point out to the customer that the doll actually did the drawing.

But the idea that a character from inside the book touched the copy of the book that you have was really interesting to me, and that's part of what went into my thinking with Hugo. The Meanest Doll in the World was a big inspiration for the illustrations for Hugo. At the end of Hugo, where we find out that the book was actually written by theautomaton that Hugo builds, is connected to the idea of Mean Mimi touching your book.The object you're holding isn't just a book; it's actually an artifact of the story itself.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What is a typical workday like for you?

BRIAN SELZNICK: There isn't really a typical workday, because the process is always changing. If I'm working on the finished drawings for a book after having done all the research and the sketches, a typical day would be painting 9:00 in the morning until

11:00 at night, with an hour for lunch usually around 4:00 or 5:00. Sometimes, I might notstart working until 10:00 or I might finish at 8:00. But it's often very long days, six to seven days a week. If I'm researching, it just depends on whatever is happening at the time. Icould be going to the library; I could be traveling.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you do when you get stuck?

BRIAN SELZNICK: If I'm working on the story trying to figure out what happens, that's probably the hardest part. I may work for an hour, then realize I have no idea what I'm doing. I may take a nap, and sometimes afterward, I'll wake up with an idea about the problem I was having. Then I'll start writing again.

Sometimes I'll just leave my house and go to a museum. I like walking aroundmuseums or walking in the park or going for a swim—just getting out of the house for alittle while and sort of refilling myself in some way.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you like to tell students and teachers?

BRIAN SELZNICK: Well, it's always interesting to talk to students and teachers abouttheir experiences with the books and their ideas about them. Sometimes when I visitschools I talk about making the books.

I'll tell students that their writing process is very similar to the process I go through:I do tons and tons of rough drafts, my spelling isn't good, the grammar is terrible—but I'm doing it to come up with ideas. Then I refine and I refine and I refine—for sometimes upto two years—until I have the text you see in the book.

The same thing happens with the pictures. I think so many kids think that you justsit down and draw a picture, but that's not the way it works. I do dozens and dozens of rough sketches before I'm ready to do a finished drawing. Talking about the processes is always interesting.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Did you expect Hugo to be popular in schools?

BRIAN SELZNICK: It was a great surprise that Hugo became something that goodteachers and librarians saw as a way to share books with kids that hadn't traditionally been excited about reading, or reading books of this size. That's been a thrill. I've had ESL teachers tell me how great Hugo is for their students, and that kids who have been reluctant readers are proud to be walking around with a 550-page book in their hands.

For me, the only impetus for making the book in its unique format was to serve thestory; this became the best way for me to tell the story about Hugo, the automaton,Georges Méliés, the history of cinema, and the art of bookmaking.

I was very conscious of wanting to really celebrate what can be done in a book.You have to hold this heavy thing. You have to open it. You have to turn the pages. It wasabout making the book.

This In-depth Written Interview was created by TeachingBooks.net for educational purposes and may be copied and distributed solely for these purposes for no charge as long as the copyright information remains on all copies.

Questions regarding this program should be directed to info@teachingbooks.net