In-depth Written Interview

with Mordicai Gerstein

Insights Beyond the Meet-the-Author Movie

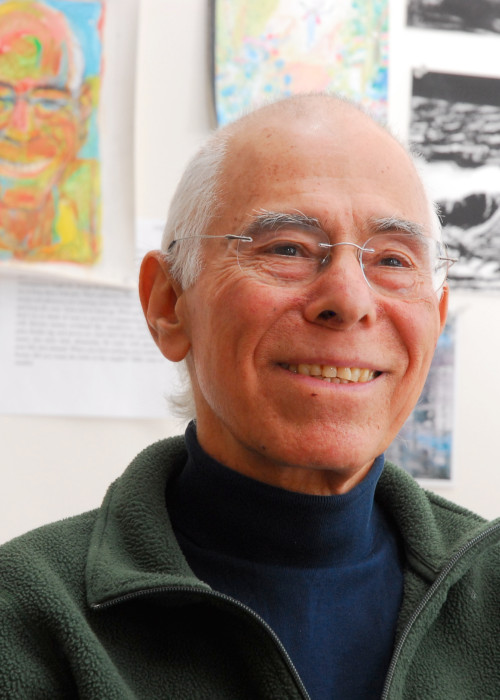

Mordicai Gerstein, interviewed in Haydenville, Massachusetts on October 28, 2004.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Your picture book, The Man Who Walked Between the Towers, won the Caldecott Medal in 2004. It's a true story about Philippe Petit who tightrope-walked between the World Trade Center towers in New York City in 1974. How did you come to write it?

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: Well, I had seen Philippe perform around New York, and he was great; he rode his unicycle and juggled torches, and he would tie a rope between two trees, jump up on it and dance and juggle up there. One day, I picked up The New York Times and saw that a young Frenchman had managed to rig a cable between the roofs of the Twin Towers and spend an hour walking on that cable. And, it just knocked me out. I thought that was fantastic. And I recognized him; I knew it was the guy I'd been seeing on the street.

I wasn't writing books at the time, but years later, there was a New Yorker article about how he had done that World Trade Center walk. That's when I started thinking about doing a story about a tightrope walker. At first, my idea was to do a story about a kid who wanted to walk a high wire. It wasn't until September 11, 2001, when the towers went down, that I remembered Philippe's walk and thought that this was a story that I wanted to tell.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What was it like to illustrate such an unusual event?

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: Every story is different, and the design of the book comes out of what the story is about, the character of the story and how the story moves and changes. In The Man Who Walked Between the Towers, I found that I did some things I'd never done before. In the night scenes, when Philippe and his friends were on the roof of the World Trade Center; it was very dark. I wanted to get the feeling of night, so for the first time I had several pictures on a page within borders, and I made the page beyond the borders a dark blue textured tone that gave the whole thing a feeling of night.

Also, since the book is about deep space and falling or not falling, I distorted the frames of some of the pictures, so they're not rectangles; they're trapezoids. I twisted the space to get more of a feeling of vertigo.

A third thing I had never done before was a foldout page that opens the book out. On the fold-out, I wanted you to feel like you were going to fall in, so I had to work on the pictures until I felt I was going to fall in, and then I knew that I was getting it. I think I've been successful, because a lot of people have told me the book makes the soles of their feet tingle when they look at it.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You got to meet the real Philippe Petit.

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: I always had a hope that maybe if I did write the book, I'd get to meet the man who did it. And, of course, he would have to like the book. All the time I was working on the book, I hadn't yet met Philippe. We'd only spoken briefly on the phone. But, as I worked, in my mind, he was looking over my shoulder saying, "No, that's not how you hold the balancing pole. That's not how you walk on a wire. I would never do that." Finally, when it was done, I sent him a copy of The Man Who Walked Between the Towers, and he liked it. And I did get to meet him.

He even wrote me a wonderful letter telling me all the things he liked about the book. He said his favorite picture was the picture of him sitting on the back of a park bench thinking about how he was going to put a tightrope between the towers, so I gave him the original painting that was used in the book.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What did Philippe tell you about his tightrope-walking experience?

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: He said the hardest thing about the walk was not the walk. He knew he could do that, because he'd trained to do that all his life. It was getting that wire stretched between the two towers in one night in the dark. He was up all night rigging that wire, which he had to walk on at dawn. And the night before, he had been up all night worrying and getting the equipment ready — making sure that everything was perfect and everything was the way it should be. And then, he was up for at least another 24 hours after he did the walk because he was in jail for a while, then he celebrated the walk once he was out of jail.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How did you decide how much of September 11 to include in the book?

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: I didn't want to go into September 11 specifically in the book, because that isn't what it was about. But, because the towers were destroyed, it is about that, without saying anything more than what I said. For instance, instead of saying, "There are two towers," I said, "Once there were two towers." Then, the next to the last page in the book says, "Now the towers are gone," and it's surrounded by white space. Opposite that text is a picture of the skyline of Manhattan without the towers. I wanted that to stop the reader; I wanted them to feel that emptiness.

When I read the story at schools, there are some young children that ask me what happened to the towers. So, that becomes a natural discussion topic, and they can talk about it and ask their parents or look in books to find out what happened.

TEACHINGBOOKS: In What Charlie Heard, you also have a page that is empty white space to signify death and change.

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: Yes, it happens in What Charlie Heard when Charles Ives' father dies. The book is full of noise; there are noises everywhere. But, when his father dies, the only words on the page are, "Suddenly, Charlie heard a great silence." And, I wanted the reader to hear that silence, so I illustrated the page with mostly white space.

TEACHINGBOOKS: The illustrations in What Charlie Heard are literally packed full of noise words.

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: I got the idea for the book from another book about Charles Ives, which started by talking about the sounds that young Charlie would have heard in his house. The sound of the church bell next door, the sounds of the wagons going by, the sounds of the grandfather clock, and I thought it'd be great to tell the story of the musician just by the sounds he heard.

Then, it occurred to me that you can't see sounds. So, I decided I'd have to write the sounds into the pictures to make a noisy book. And when I showed it to my editor, she thought I was very brave to write all over my pictures: to write "bang, crash, clash, moo, bong, kaboom, kapow," and all these other sounds. What Charlie Heard was a very challenging book to make.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You also wrote and illustrated a book about John Bardsley, the man responsible for the English sparrow's existence in North America.

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: Yes, Sparrow Jack is about the man who brought a thousand English house sparrows to the United States. He brought them over so they could eat up the inchworms that were destroying all the greenery in Philadelphia. And they did. And now we're stuck with sparrows everywhere.

It struck me that America is an immigrant country, not just for different kinds of people but also animal immigrants that have been brought over from Europe and Asia — different kinds of cows and pigs and ducks and chickens, brought over to do different kinds of jobs. So, the story of the sparrow is a way of thinking about animals as immigrants and human immigrants, as well.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Wild Boy is another biographical picture book.

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: One of the reasons I was drawn to the story of Victor, the Savage of Aveyron, was his wildness and the opportunity to draw him as being wild. My drawings are about feelings, so in this case, I wanted to get the feeling of being wild. I wanted to know what it's like to be wild, so I had to imagine what it's like to be this kid. I don't use models of real people; I imagine that I'm the person and try to draw the feeling. So, the first part of the book, where he's wild and dancing in the snow and looking at the moon and drinking water from the stream were really fun to do, because I wanted to feel what it was like to be that kid.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Did you step into other characters when illustrating them as well?

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: Yeah. One of the wonderful things about making books is you get to find out what it's like to be someone else. That's the great thing about reading, too. One of the reasons we read is that you get to live a whole different life by reading about someone in a book. And, you get to know what it's like to be a different creature.

It's true with The Man Who Walked Between the Towers. That's the closest I'm ever going to come to walking on a high wire. By writing about Philippe, and especially by making the pictures, it was like being on the high wire for me.

And in my other books, too, whatever the character's doing, I'm doing that. I get to see what it feels like to be Arnold who's raised by ducks. To see what it feels like to be Sparrow Jack, to care about your old friends the sparrows and want to go and bring some home. This sentiment is one of the reasons I wrote The Old Country; I wanted to know what it was like to be a fox. So I wrote a story about a girl that becomes a fox. It's a great way to experience another way of being or of living more than one life.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Please say some more about your latest novel, The Old Country.

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: It's the story of a girl who is a fox and of a fox that is a girl. The young girl all of a sudden finds herself in the body of a fox and this fox has stolen her body. So, the fox goes home and sees what it's like to be a human being and have access to all the chickens that this girl's family has.

The Old Country came out of several ideas that have been simmering in my mind for quite a while. I love foxes, and from time to time I run out in the country and through the woods. On a couple of occasions, I've met foxes. Once, I was running along a little trail through the woods and I came around the bend, and there was a fox right ahead of me that didn't know I was there until I came up quite close. Then, it turned around and looked at me, and we looked at each other, and I think the book started at that moment. Foxes also make me think of fairy tales and the old country. I mean, the old country to me is the country that my grandparents came from, and it's also the place that fairy tales came from.TEACHINGBOOKS: When you say "the book started at that moment," what happened?

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: I had a feeling about the story, and the characters I wanted to tell. More than any other book I've written, The Old Country kind of wrote itself. One event followed another, and I was amazed. Usually, I struggle with plot and I don't know what's going to happen next, and I have to wait and I have to try out different things. In this case, the story just galloped ahead and I was amazed at the things that happened and really surprised at how it ended.

I didn't know that writing could be that way. I thought you had to know the whole story when you started, and then you just kind of write it down. But it doesn't have to work that way. Sometimes, you just write and write and write and find out what the story is.

TEACHINGBOOKS: The Absolutely Awful Alphabet is a zany take on an old standby.

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: The Absolutely Awful Alphabet came out of something my cartoon teacher, "Thee," said about characters: that they should be as interesting and different from each other as the letters of the alphabet. And I thought, "Wow, that's a great way to look at it." Then, I looked at the letters of the alphabet, and I saw that A was very different from B because A was kind of like a little house and stood up straight. B is bumpy and bulgy. C looks like a big mouth about to eat something. I thought about that for years.

I always like to doodle, taking letters of the alphabet and turning them into different kinds of creatures or monsters. At some point, the idea came to me that this could be an alphabet book and I'd turn each of them into a different comical monster. And, since one came after another, I thought maybe they could have something to do with each other. So, it became a story — a story in one sentence. I had a lot of fun doing that book.

TEACHINGBOOKS: It sounds like "fun" is integral to your approach to life.

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: Well, I believe that life should be fun. My work is fun. Sometimes I have to do more of it than I want to at any particular time, but I really believe in having fun, doing the things that I enjoy and pursuing the things that are interesting to me — which are a lot of things.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How did you get started in children's books?

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: I had never really thought about doing book illustration or doing children's books until I met Elizabeth Levy in 1970. She was a young writer and I was still doing animated cartoons, sculpture, some newspaper and magazine cartoons and illustration. I met Elizabeth at a party, and she asked me if I would like to illustrate a story she had written. She asked if I'd draw some characters for it and see if we could sell the idea for a book. And I liked the story: it was mystery about two little girls and their dog who never moved. So, I did the drawings, she took the drawings and the story to an editor she knew and the editor called the next day and said, "This is just what we're looking for." So, all of a sudden, I was a children's book illustrator. That book became the first in a number of series, the most recent of which is called the Fletcher Mystery series. [Editor's Note: See the bibliography at the end of this document for a complete listing of Fletcher books.]

TEACHINGBOOKS: How does collaborating on a book differ for you from writing and illustrating on your own?

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: Well, as an illustrator, collaborating with another writer is not so different from illustrating my own stuff because, when I write, I write as a writer and I don't think about the pictures. I try to get the words right, and get the whole story into the words. Then, I forget that I was the writer, and I pick it up and read it as an illustrator and I think, "Wow, how am I going to draw that?" I've got to be able to see pictures when I read it as an illustrator. There's got to be something that I can visualize for me to want to illustrate it. So, that happens whether it's my own book or someone else's.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Your first written and illustrated book was Arnold of the Ducks.

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: Yeah, I worked on the story for a long time, so I was very proud of it. Arnold of the Ducks was about a boy that was raised by a mother who happened to be a duck. He was carried off out of his wading pool in his back yard, fell into a wild duck's nest and was raised with a little flock of ducklings. He grew up thinking that he was a duck, and the other ducks accepted him. He learned to fly. It was fun doing that, because I didn't know when I started the story whether he'd learn to fly or not, but I decided that he so believed that he was a duck that he could fly. Later, he had to come to terms with his being human.

TEACHINGBOOKS: One of your more enduring early books is The Mountains of Tibet.

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: Usually a book comes from maybe two or three different things that kind of come together at a certain moment. And years before I wrote The Mountains of Tibet, I had been reading this ancient Tibetan book called The Book of the Dead, which was kind of a "how to" manual about dying, which sounds kind of morose. But, it was actually fascinating, because it tells you exactly what is going to happen to you at every moment before you die, and after, and all the things you are going to have to face and deal with. That was one part that came together to inspire the book.

Years after reading the book, I was about to get married for the second time and begin a new life, so I thought, "Well, here I am starting a new life." It's like kind of reincarnation without having died, and I remembered the book about reincarnation, about living another life. I thought about all the choices I'd made that brought me to this day —my second wedding day. The idea for the book came at that point.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Your picture book, The Mountains of Tibet is thought provoking and raises many questions among readers young and old.

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: That's very good, because I really think that a good book provokes and gets the reader to ask good questions. That's what I think a book is for, ideally, not to give people answers, because answers should always be questioned anyway. I want people to ask questions.

The Mountains of Tibet asks questions about what happens after you die. What do you think about reincarnation? Do you think that's a good idea? Do you think it's something that might really happen? What would you, if you had a chance to live your life again as any kind of creature, what kind of creature would you choose and why would you choose that? And if you could live anywhere you wanted in the world, where would you live? And if you choose your parents, whom would you choose?TEACHINGBOOKS: Do your books contain any common threads or central themes?

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: This is something I was thinking recently, that all stories in one way or another are about this mystery of being a human being. Questions like, "How do you do it?" "What are we here for and what are we doing?" "How am I supposed to be a kid?" "How do I be me?" I think all my stories are about that.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Describe a typical workday for you.

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: I work five days a week, Monday through Friday. I get up at 5:30 in the morning and I bicycle to work. If it's a good day, I might bicycle as much as 12 miles to work and take a lot of detours and go up some pretty roads. If it's a cold day and a winter day, it'll only be six miles. I stretch my legs out for a little bit, I sit down and I go to work. If I'm writing something, I'll write in the morning until Noon, and then I'll stop for lunch. In the afternoon, I'll do my illustration. I'll be writing one story and illustrating another one. I usually knock off around 5:00 or

5:30. That's pretty much my day.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you do when you get stuck?

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: If I'm stuck writing a story, and I don't know where to go with it, I'll work on my illustrations. Or, I'll start another story and put away the one that's stuck until it gets unstuck. There's always something else to do. Or, I'll just take a bicycle ride.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you like to tell students?

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: When I go into schools I tell kids about me, but I like to tell them about them, tell them about their own imaginations. I like to tell them about the stories that are in them that they don't know are in them. I like to talk about the pictures that they're going to make that they don't know they're going to make. And, that they have tremendous power. They have the power; everybody's imagination is huge. They just have to get in touch with it.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Were you encouraged to be creative as a child?

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: Yes. As early as the age of four, I can recall lying on the floor in the living room and looking through a scrapbook my mother made me. She cut masterpieces and famous paintings that were reproduced in Life magazine — da Vinci, Blake, Picasso, Matisse.

I still remember a lot of them. And they really became part of me. When I illustrate, I find that almost every picture I do is connected to some picture I've seen during my life, and maybe even some of those I saw as a kid.

Both my parents were very happy when I started to draw. They both really loved art. My mother had a very sophisticated eye, and my father was trying to support the family and be a playwright at the same time.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What did you do before becoming a children's book creator?

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: I went to Saturday art classes all through my growing up. And then when I got out of high school I went to an art school in Los Angeles that was connected to Disney Studios.

I never really dreamed of being an author. Always it was the pictures that I was connected to. I loved reading. I loved stories, and I was in awe of anybody that could write stories. But, I had no clue as to how to write stories or that I could write them. I didn't even really think about it, since doing cartoons and illustrating somebody else's stories was my job.

There was also a whole period of time where I did assemblage sculpture when I was living in New York City.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You seem to truly enjoy the process of creating picture books.

MORDICAI GERSTEIN: Part of the fun of doing a picture book is designing it — designing how you get from one page to the next page, and how you put the pictures next to each other on two facing pages to tell the story in the most effective way. And every time you turn the page, you want it to be a surprise of some kind, something a little unexpected, something that leads you to turn the page again. Also, there should be a variety in the pages and the story; some pages you're going to spend a lot of time looking at, and some are going to go more quickly so that there's pacing and timing like there is in a movie.

I am also interested in the borders of the illustrations; sometimes I like to have my pictures go off the page. It's called bleed pages where they continue right to the edges. But more often, I like to contain them so that they're on the page and you have the whole picture right in front of you.

Finally, making a picture book is fun because you can do anything you want. You've got blank pages, you've got the story, you've got words and you've got pictures. You can do anything you want to tell this story in the best way you think you can tell it.

This In-depth Written Interview was created by TeachingBooks.net for educational purposes and may be copied and distributed solely for these purposes for no charge as long as the copyright information remains on all copies.

Questions regarding this program should be directed to info@teachingbooks.net