In-depth Written Interview

Insights Beyond the Meet-the-Author Movie

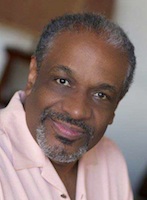

Christopher Paul Curtis, interviewed in his studio in Windsor, Ontario, Canada on April 22, 2002.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Your books are funny despite their serious subject matter. How and why do you use humor in your children's books?

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: I think humor is something that is universal. It is something that is very welcoming. When I write, I want to pull readers in. I want to get the kids interested in what I have to say. I look at life in a very humorous way, which can be a problem some of the time — not everything is humorous. When I write, I have a riot. When I sit in the library, I'm really focused on what I'm writing. I have my head down writing away, and I'm laughing to myself. I'm getting a lot of strange looks if there are people who don't know who I am.

One of the things that humor lets you do is to vent. I'm not sure who said it, but humor is always based in tragedy. For any joke that you can think of there's always something very tragic going on, if you break down what's happening.

Humor and tragedy go hand in hand. I think humor is a way of coping with tragic things; humor naturally elevates us away from the tragic. Plus, if you start reading something and it is funny, then you're hoping that the next joke will be a little funnier, and the one after that a little funnier. And hopefully, before you know it, you're hooked on the book and you're empathizing with the character. You want to see what happens next.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Music is another theme in your books. This must be very important to you.

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: I love listening to music. It touches something very deep inside of us. Sometimes I get the same feeling after writing as I get when I listen to a really good piece of music. It takes you somewhere else. It takes you out of yourself and opens up something mysterious.

Kenny was kind of hooked on Yakity Yak. That is sort of like me. I get hooked on a song; I listen to it over and over and over. With The Watsons Go to Birmingham, I was listening to a song by Stevie Wonder called, I Wish. I think some of the flavor of the song made it into the book. In Bud, Not Buddy, I was listening a lot to Betty Carter who is a singer from Detroit. The song that I played over and over and over was called, I'm Yours, You're Mine. I drove my family crazy. While writing Bucking the Sarge, I got hooked on a song by a Canadian musician (Bruce Cockburn). The song is called, If I Had a Rocket Launcher. I worked that into the story as well.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Are there any characters in your books that you've pulled directly or indirectly from your life?

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: In writing Bud, Not Buddy, I was able to use characters that were based on my grandfathers. Herman E. Calloway is based on Herman E. Curtis. And Earl Lewis is based on my grandfather, Lefty Lewis.

The scene in The Watsons Go to Birmingham, where Miss Henry takes Kenny around and shows his reading skills to the other children, that happened to me. One of the really fun things about writing is you can thank the people who have made a difference to you. My teacher, Ms. Emery, would take me to different classes and have me read to them, and even have me read upside down.

As a writer, you can bring things like this into the story. It makes it more vital. It makes it more real.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What's important to you about including bullies in your books?

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: I think that, as a young person, bullies are probably the first real threat to you from the world. It's kind of the first message from the world saying that everybody is not your mother and your father. Everybody doesn't think that you're this wonderful, great person. Welcome to the real world. So, in both The Watsons Go to Birmingham — 1963 and Bud, Not Buddy, when the boys are bullied, that is the beginning of their growth.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How do your story lines and real life merge?

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: I think, as a writer, you have a unique opportunity to work out things that are going on in your head or to rearrange things that you've thought about to make them come out in a way that you want them to. You are very powerful as a writer because you can create people. You can destroy people. You can do just about anything.

The Watsons Go to Birmingham — 1963 was originally called The Watsons Go to Florida — 1963. The story was pretty much the same with a juvenile delinquent going to his grandmother's in Florida. But, once they got into Florida, the story died. It just ended right there. I knew there was something wrong with it, and I set it aside.

Then, my son brought home the poem, Battle of the Birmingham by Dudley Randall, about the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church. As soon as I heard it, I knew the family wanted to go to Birmingham.

Fortunately, as a writer, you can wait. You can use time. You can have things that happen, like a poem that comes into your life that you can incorporate into a story. I think that makes a real difference. I think The Watsons Go to Florida would not have been quite the story that The Watsons Go to Birmingham is.

With Bud, Not Buddy, I wanted to do a book about a sit-down strike. The factory that I worked in had a sit down strike in the 1930s. So, I did a lot of research on the '30s. I had that done. And then I went to a family reunion in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and they started talking about my grandfather who, in the 1930s, had a big band called, "Herman E. Curtis and the Dusty Devastators of the Depression." So, of injected itself into the story. And, soon it became a story of an orphan instead of a strike. Where he came from, I have no idea. But that's where that story developed.

A lot of times, as a writer, you hope for these volts of inspiration to hit you from out of the blue. One of the things that I tell young people is, "Don't worry, something will happen. Something will come along that will lead the story down the way that it is supposed to go."

TEACHINGBOOKS:What else do you like to tell students?

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: I tell them how old I was when I started seriously writing. When they find out that I was 40, hopefully that gives them a reason to think, "Maybe, if I stick with my dream, do what I have to do to live, keep that dream alive, keep it going, maybe things will happen right for me."

Also, I think students get tied up with thinking, "Oh, I've got to start at the beginning and work all the way sequentially through to the end. And, finally, the last thing I'm writing is the end." But it doesn't work like that for me. I think the first thing I wrote for The Watsons Go to Birmingham was the scene where Byron gets his lips frozen to the mirror. When I finally put the story together, I had it somewhere in the middle of the novel. When I write, I really don't know where the story is going or where any particular scene is going to fit into the final story.

I think the important thing is to get it down. Get the story rolling. Ideas are like seeds. You start one, you don't know exactly where it is going to end up or even if it will be a part of it.

And finally, I tell students that there's no greater feeling than to be able to make a living doing something that you love. It's just the greatest feeling in the world. And take that from somebody who has had a lot of unpleasant jobs.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you hope children will take from your books?

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: I think that the best that children will take away from my books is that it piques their curiosity. That it makes them want to know what was going on in the 1960s. Why there was this big fight for Civil Rights? Hopefully, it will have them go read another book or do a little research and find out what exactly was happening. The same with Bud, Not Buddy. I hope that by becoming Bud's friend, in effect, that by traveling on the road with Bud and being in the bushes hiding, not knowing what you are going to do next, I hope that it gives children some kind of perspective as to what it was like at that time.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Do you have a special hope for African-American readers?

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: Hopefully my books can provide some kind of entrée to young black kids, and to all kids really. But particularly to young black kids, where they have somebody that they can look at and say, "You know, that's me. That's something dealing with me." The books are about African-Americans. And, hopefully, it touches all kids in a special way, but particularly African-American kids.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Are there any children's authors whose work you particularly admire?

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: I think that Walter Dean Myers has done something that is groundbreaking for me. There are things that he has done that if he hadn't have done them, it would have been a lot harder for Christopher Curtis and for other African-American writers to come along. So, I have a lot of respect for him as a man and also as an author. I think Monster is one of the best books I've ever read.

TEACHINGBOOKS:You show a respect for teachers in your books.

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: The job that teachers do is tremendous. There is not enough pay. There is not enough support. It's just a tremendous challenge and it's a tremendous job. I don't think teachers hear that enough that people do appreciate all the work that they do.

Unfortunately, sometimes the teacher is the only positive supportive person that a lot of children are going to see during their day, during their life. I don't think teachers get anywhere near enough thanks or respect for all they do.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How did you come to be a writer?

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: I never really thought of the possibility of writing as a profession. But, my wife had read stories that I had done, and she felt that I had a skill as a writer. So, we worked it out so that I was able to take a year off work. And I would go to a public library, and I would sit and write every day. Even then, I wasn't thinking that I would make a career of it. My wife gave me a shot at having the ability to do something that I wanted to do so that when I got to be sixty or seventy years old, I didn't have to say "what if" or "maybe if..."

I was very fortunate in that Kay had the foresight and the courage really to give me the time off work to take a chance on my dream, and to try to follow through and see if I could be a writer. And I didn't look at it as a chance to become a professional writer. I just thought that if I take this year off, I could see what I could write, what I could do.

A lot of times when you tell people you're going to do something, to follow your dream, you sound pretty ridiculous in their eyes. I can recall going to a party in Toronto. People started telling what they were doing for living. This was about halfway through my year of being a writer. They were going around the group, and they finally got to me. I said, "I'm a writer." And you could see the looks of sympathy from the women going to Kay. But Kay said, "Oh yeah, he's a writer. He's a very good one. One day you are going to hear about who he is."

TEACHINGBOOKS: Did you read much as a child?

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: Reading and books were very important in my parent's house. Both of them were avid book readers. I, on the other hand, was not a book reader — I read magazines and newspapers. Mad Magazine was one of my favorite comics books. I also read sports magazines and National Geographic. I read just about every magazine that there was. I was always a good reader, but books didn't grab me when I was younger. I wasn't a sophisticated enough reader to really enjoy the James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison type books. It wasn't until I was eighteen and working in the factory that I really started to love books.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Did you write while working in the General Motors factory?

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: Yes. My job at the auto factory was to put doors on cars. It was very heavy, very demanding and very repetitive. We would hang three hundred doors a day each. They weighed anywhere from fifty to eighty pounds. I was in great shape, but mentally I was toast, because I was doing the same thing over and over and over. It really got to me. The solution that a friend of mine and I came to was, instead of hanging every other door like we were supposed to, he would do thirty in a row, and then I would do thirty in a row. This way we each got time off the line to do whatever we wanted to do.

That's really where I started to get the discipline to write because I would spend my time writing. It was therapeutic for me. I'd forget about the factory. Time would go by really quickly for me. The next thing I knew I was back up, you know, and while working I was thinking about what I was going to write next. So, that kind of worked out really well for me like that.

TEACHINGBOOKS:Could you describe a typical day of writing these days?

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: I divide my writing life up into two parts. I have the creative part and then I have the editorial part. Usually, in the mornings, say about 8:00, after I drop my daughter off at school, I'll go to the library to write. I'll sit in the children's section of the public library. I just sit down and I say hello to all the people I know, and chat for a little while with whoever is there. Then I get into the process of writing.

I have found that it is important to me to just let it come. I don't try to form my writing into a shape of a story. I don't try to say, "This won't work. Let me stop. Let me go on to something else." I just let the things run off on whatever tangent they want to run off on. Then the next morning, I wake up at 5:00. That's when I do the editorial part. I'll sit and try to cut out the parts that I wasn't able to use from the previous day's writing. I try to beat the story into shape. I found it is necessary to really make a division of the labor, and have Christopher the writer just sitting there having fun doing whatever he wants to do, and leave the hard work to Christopher the editor.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you do when you get stuck?

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: I don't know if it is from all the time I spent writing in the factory or if I've really convinced myself that there is no such thing as writer's block, but I've never really gotten to the point where I just couldn't go on because the story didn't seem to flow right. I think if that happens, you just have to start back tracking. Somewhere there is a point where you went wrong. Find where you made the wrong turn, and then get back on track.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What else can you share about your writing process?

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: I like to have two or three things going on at the same time, because I get tired of writing one thing. And sometimes, what I'm writing doesn't seem to be going the way I want it to go. So if you have other things that you're working on, they tend to take over some of the time. That's what happened in Bud, Not Buddy. Originally, the sit-down strike seemed like a really good idea, but then this orphan's voice started coming to me. This story that incorporated parts of my grandfather into it just took over. I think that you learn after a while that you don't try to interfere once you start hearing these voices. It's kind of scary, but once you start hearing them, you listen to what they say.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How do you work foreshadowing into your books?

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: I write the entire piece, and then I can go back in and put in a little piece here, a little piece there, that kind of piques your interest.

I think a lot of foreshadowing is musical, almost. I've noticed that composers give a little inkling of what is going to come. It makes you really aware and appreciative on second reading or second or third listening. In some Beethoven pieces, the Ninth Symphony in particular, there is foreshadowing of what's to come.

A lot of the jazz people, such as Miles Davis, do this quite a bit. It's something that I think can translate easily into writing, and it has to do with the fact that you're a composer and that you have the time to go back and look at what you've done. Repair it. Edit it. Make it better. Editing is the hardest part of writing, but it's the most important part because that's where you really can add the punch and can make it something special.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What can you share about your next novel?

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: I just finished a book called Bucking the Sarge. It is the story of a fifteen-year-old boy from Flint, Michigan. His mother owns a lot of rental properties, group homes. She's a real hustler. She's trying to make money. She's a scam artist. She's cheating everybody she can possibly cheat: the clients, the government, the insurance companies...

She looks at life as a challenge, and that to win in life you have to take advantage of everything that you possibly can. So, she's finding ways to slither through every loophole that she can, and she's trying to train her son to take over the business. She feels that it's important for him to have a leg up and to understand how the system works in her eyes.

He has a lot of troubles with this because he wants to be a philosopher, even though he knows that doesn't pay very much money. It's what his career choice is. So, they have a lot of conflicts.

I had a lot of fun writing Sarge, but it took much longer to write than the other books. It was different for me because it wasn't a ten-year-old narrator this time. The boy is fifteen. And, Sarge is a contemporary story where the first two were historical.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How do you respond to requests for sequels to your first two novels?

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: I think certain books lend themselves to a sequel. I think Bud, Not Buddy is probably more the kind of book that needs a sequel rather than The Watsons Go to Birmingham. So, one of the secondary things that I've been working on when I was working on Bucking the Sarge was a sequel to Bud, Not Buddy.

And then, as a special challenge, I was trying to do a story from the perspective of one of the girls that's in the book. Deza Malone is this girl that gives Bud his first kiss. A lot of times when I go out to speak to children, I get a lot of feedback from the girls in the audience. They want to know how come I don't do a book about girls. Then there are a lot of questions about Deza, and something about that character interested them. So, I have started to try to develop a book done from Deza Malone's point of view.

TEACHINGBOOKS: On the day of this interview (April 22, 2002), The Windsor Public Library named the children's section of the library the Christopher Paul and Cassandra Curtis Learning Center. How does this feel?

CHRISTOPHER PAUL CURTIS: It's a tremendous honor. It's the place that I first wrote my books and where I continue to come to finish my books. To be associated with the library in such a way, something that is so important; it is a wonderful feeling.

This In-depth Written Interview was created by TeachingBooks.net for educational purposes and may be copied and distributed solely for these purposes for no charge as long as the copyright information remains on all copies.

Questions regarding this program should be directed to info@teachingbooks.net