In-depth Written Interview

with David Small

Insights Beyond the Movie

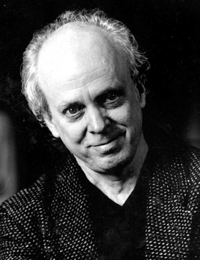

David Small, interviewed in his studio in Mendon, Michigan on May 18, 2002.

TEACHINGBOOKS:TEACHINGBOOKS: You and your wife, Sarah Stewart, have written and illustrated a number of books together. What is it like to work so closely with your spouse?

DAVID SMALL: I think Sarah and I both come through very clearly in all of the books we've done together. We are different from one another, with very different outlooks and very different opinions. And yet, there's a tremendous respect for each other's outlook and opinions.

Her books are difficult for me to illustrate, but always more satisfying than any other projects, if I can do them right. And so far I feel I have. But in some ways it's a grueling experience because I have to put aside my city boy cynicism to a certain extent and accept her optimistic, hopeful attitude toward life. This is always a healthy experience for me. But on the other hand, I think that I provide Sarah with a dose of hard-nosed reality about people and things.

We don't "collaborate" on books the way people may imagine. She is in her world, and I am in mine. I may occasionally ask her for criticism on a drawing or a painting. But for the most part, I rely on my editors and art directors for that kind of response.

The books that I've done with Sarah are really acts of love. And I think that accounts for their depth, their complexity and their soulfulness.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What role did art have in your life when you were a child?

DAVID SMALL: I feel that if I had not had an art program in my school, I would have failed in a big way. My teachers knew I was intelligent, but they didn't quite know how I was ever going to apply that intelligence. The one or two teachers who knew me well knew that it would be through drawing or acting or whatever means of expression I was allowed.

I had a really wonderful art teacher in grade school back in Detroit. She was very encouraging to me, and she gave me some challenging exercises that would probably, even today, be considered too challenging for a child.

I feel sorry for kids nowadays, because in the majority of schools across the country, the arts have been eliminated from the curriculum. There's no art; there's no music. In some cases they've taken away the libraries. They don't do theater. And these are the things that speak to the human soul.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You were an art teacher for many years. What was that like?

DAVID SMALL: When I was a teacher of art, I wanted to do what my best teachers had done for me, which was to simply convey my passion for the subject. I figured if I could get that across to students, then the details would follow.

I found great value in teaching students from the outset of their studies how to draw very realistically. Otherwise, you're starting deep into the alphabet instead of having started at the start. If you discard essential things like drawing, design, color and so on at the beginning, then you're just sort of floating out in space, without any basis to work from.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You haven't always illustrated children's books. What kind of art did you create early on?

DAVID SMALL: I supported myself for many years doing editorial art — those little black and white or color spot drawings that accompany an editorial article in a newspaper or magazine. These works kind of sharpened my artistic teeth, because I had to have a quick response to an article, whether it was a piece of political commentary, or a theater review, or a movie review. I learned to quickly make up my mind and get the thought down. This was also a chance to develop my skills as a social satirist. So in these ways, this was very satisfying.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Are you still interested in creating a commentary with your artwork?

DAVID SMALL: My interest really is psychology, what's going on in people's minds as revealed on their faces and in their posture. That is my strength. And it's something that came from probably being a silent observer for most of my life and having to read what was going on in people's minds from only their postures or from their expressions.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Can you give an example of a specific posture in a book illustration?

DAVID SMALL: There's a picture of mine that's become fairly well known out of The Gardener. It's a picture of nine-year-old girl Lydia Grace, who has just arrived in New York City. She's ridden the train by herself. She's come from the country and into the city for the first time. She's standing alone in Penn Station. And she's looking around her at this huge environment. She's just set down her bags, and there's a certain tension, perhaps, in her body as she stands there, sort of rigidly looking up into this cavernous darkness around her.

But there is also a feeling of strength there, and resilience that comes from who she is. This child is alone. But somehow, if I've done my work right in doing that, in drawing her in that posture, you're not going to be that afraid for her, even though she's in a rather dark and threatening environment.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Environment seems to be an important part of what you focus on in your book illustrations.

DAVID SMALL: Yes. For example, what I was after in the illustrations for The Journey was a sense of silence. It was really sound more than anything that drove those compositions — the striving for a sense of what happens to people from the city who visit out here in the country where we live (rural Michigan). There is a profound silence here that keeps people awake sometimes when they first come here. The silence is deafening. And yet, Sarah and I live out here with it all the time. And we find exactly the opposite to be true — that when we go into the city, we're disturbed by the noise.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Did you always want to be an artist when you grew up?

DAVID SMALL: I grew up going to the theater. That was one of the nice things my mom did was she took us to plays and symphony concerts and to the museums. Theater captured my imagination. I just loved the idea of that box, which is essentially what a stage is from a certain distance, a box with all this life going on in it. So, I was eleven when I wrote my first play. Of course, it was horrible.

But by the time I was seventeen, I had three plays produced by a little resident professional company in Detroit. They probably weren't much better, but by that point I had some favorite playwrights that I was imitating, which is how we learn. And by the time I was twenty-one, I thought I was going to be a writer, but then a good friend of mine did me a favor.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What was the favor?

DAVID SMALL: He informed me that, in his opinion, my little doodles were so much better than anything that I'd ever written or had performed on stage. He advised that I go into studying art, which at first shocked me because art was so easy. It was just something I did, like breathing or brushing my teeth. It couldn't be a job. I had a much more difficult time writing plays, making myself sit at that typewriter and finish those things.

I think the most critical thing about my playwriting phase is that I actually did make myself sit at the typewriter and finish those things. So, even though I didn't become a playwright or even a writer, in a major way, I learned the work and the discipline of taking something from the beginning to the end. And I think that's very important.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You are a voracious sketcher.

DAVID SMALL: I think some of my best work is done in my sketch journals. First of all, I carry one all the time because I want to record where I was and what I saw, but also some of what I was thinking about, what I was looking at. For me, a camera is highly unsatisfactory for that purpose because a camera takes in everything with the same sort of blunt swallow and doesn't evaluate anything except in the way you frame it.

So, when I look back on a sketch from a landscape or a bunch of people or a restaurant I happen to be sitting in, it doesn't matter how much time passes. I open that journal, I look at that picture and I remember where I was. And I remember the time of day, the temperature of the air, what music was playing, or who was talking to me, or who was looking over my shoulder and what conversations we had and the smells of the earth and the time of year it was. It's all there for me in a way that we don't get looking at a snapshot. Most of us look back at a snapshot from ten years ago and say, where was that? We don't even remember where we were.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What is The Journey about?

DAVID SMALL: The Journey is a kind of "there's-no-place-like-home" story, wherever home happens to be. It's the journey of this young Amish girl, who has never seen the city before, sees it for the first time, falls in love with it, is absolutely enthralled with all the wonderful things in this sort of alien civilization that she's always lived on the fringes of. And she's sort of taken with it. Perhaps there's some tension in thinking that she might be drawn into it permanently. But in the end, she chooses really what she's familiar with.

TEACHINGBOOKS: And The Library?

DAVID SMALL: The Library is about obsession. This woman, Elizabeth Brown, really has no exterior life. She just reads to the exclusion of everything else and, from an outside point of view, may look like a total loser. But in the end, she makes a real contribution to the world because of her obsession. She's semi-comical, and yet there's also something fierce and frightening to me about Elizabeth Brown. She's a very strong character, and she's following her own drummer. Sarah and I have different views on her.

Sarah's view of that character, I think, is that her life is mostly inner and very, very rich. And the life of the mind in seclusion is very, in some ways to her, heroic. Sarah, herself, has no trouble curling up in a room with a book and doing nothing else for weeks at a time. And it doesn't look to other people as if anything's going on. This person is walking around, chewing on a pencil, staring out the window, and, there's a lot going on. You just can't see it.

I wanted to show what others might feel about that too because that's what the illustrator has to do.

TEACHINGBOOKS: It appears from visiting you and Sarah Stewart that you live among gardens much like the gardens that Lydia Grace Finch created in The Gardener.

DAVID SMALL: The gardens that Sarah has created around our house, on our land, have really shown me that there is an art there that I couldn't perceive before. It's a canvas that's constantly changing in its colors and its shapes, all season long. And it's not something that happens spontaneously. It takes a lot of planning and a lot of work, physical and mental, and the same kind of work that one puts into a painting. It's the same kind of organization; it's just on a larger scale. It's like painting. It's like music. It's like sculpture. It's three-dimensional. It moves around you. It makes sounds. It moves. It's kinetic. It's amazing. And Sarah taught herself this, basically. She's a self-taught gardener.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Your illustrative style is dramatically different in The Money Tree. Explain.

DAVID SMALL: I rearranged my entire artistic style in order to try to illustrate that story the proper way. It's a much more realistic style than I ever used before. I wanted anybody who knew anything about flowers to be able to open up that book and say, that's a day lily, or that's a bunch of this or a bunch of that.

I think The Money Tree is an extraordinary story, and I feel privileged to have been part of that process of making it. It required me to work very hard to try to persuade the viewer without any words at all that this woman's life was better without that money tree than it was ever going to be had she accepted it or gotten involved with it.

TEACHINGBOOKS: The message of The Money Tree comes across clearly in the finished book. What in the illustrations did you feel you had to show?

DAVID SMALL: I think if you had the experience that I had — if you just had the text with no pictures, you would see that the story does not really give you the answer — it doesn't tell you why. It's all there, but it's very subtle.

I was rather horrified actually, when a friend of ours, also an author, took a look at an early version of the book and came to the conclusion that the woman was a fool, that she didn't even know that there was money on the tree. And that's when I tore the book down and redid it for the third time, because I didn't want there to be any question of the intelligence of this character, Miss McGillicuddy. I wanted it to be clear that she had made a very intelligent choice to stay away from that tree.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How would you describe the illustrative style you used for So You Want to Be President?

DAVID SMALL: My style really loosened up with So You Want to Be President?. I just did it without any going over, without throwing too much away. I just started cranking out the drawings. And if they worked, they worked. I was really flying. And it was fun. It was exhilarating. I just threw caution to the winds and just started having fun with my drawings and using every material I felt like, a little bit of chalk, some watercolor, pen and ink, colored pencil, whatever was at hand.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What was your initial reaction to the manuscript for President?

DAVID SMALL: The manuscript for So You Want to Be President? appealed to me because there was a chance to talk about and show the presidents as human beings — to show more than just the men in power, to show them as guys who put on different colored socks in the morning, or dived into an empty swimming pool, or what have you. By the time that book came along, we had already had enough presidents that had shown us that presidents are human beings. So I felt I was contributing to the common knowledge there, but not revealing anything really new — sort of supporting what everybody already was suspicious of.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What can you share about your illustration of President Taft?

DAVID SMALL: It was fun doing Taft being lowered into his bathtub by a crane — a very absurd situation, which I think I somehow made believable. I don't know if you can get a crane that size into the White House. But, I very conveniently cut it off at the top so you only have to imagine how really tall it is. And those butlers, with their gestures, show a very realistic portrayal of what guys do when they're trying to guide in an airplane or a big operation like that.

I was very pleased after the book came out. An old history professor friend of mine wrote to thank me for doing this illustration of Taft the way I did because it reminded him of photos that he remembered from his childhood. They showed Taft being hoisted aboard a ship by crane. He was sitting on a big board that they would lift up, because he was too fat to get up the gangplank.

TEACHINGBOOKS: And yet So You Want to Be President? has some very serious moments as well.

DAVID SMALL: One of the glories of doing this book was the shifts in tone, where I was able to be humorous and then very serious. And the impeachment page is certainly the best example of that. I didn't have to think too much about how to present this one. I got the idea right away that a good way of showing the shame of President Nixon would be to put him down in the shadows under the Lincoln Monument, with Lincoln sort of glaring down at him from an elevated, better-lit position.

I had to redo the illustration a number of times because, as I was working on this very painting, the Clinton presidency was going down the tubes with the Lewinsky scandal and so on. So I knew that I was going to have to work President Clinton into the picture somehow. The author, Judith St. George, changed her text to accommodate it as well.

But at that point, we didn't know where Clinton was going to end up, whether he was going to be down there at the very bottom in the shadowy realm that Nixon will forever inhabit, or what. So I put him halfway down the stairs, thinking that he was certainly on his way down at that point. And as it turns out, that was the perfect place for him, because that's where Clinton has stayed — sort of halfway to the bottom, not all the way.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What kind of research did you do for President?

DAVID SMALL: I had tons of research material. I had the official portraits of the presidents. I had all the photographs I could find of the ones who were photographed. Sometimes there was nothing but the official portrait to go on, which was sort of hilarious, trying to glean the psychology of somebody from those stiff, posed, academic oil paintings. Oddly enough, finding the psychology of those guys in those paintings, especially put together with their biographies, was great fun. I didn't go to Washington or visit the White House until after the book was done, but it was interesting to see what I was able to get about those places from my research materials.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You and Judith St. George then collaborated on another So You Want to Be book.

DAVID SMALL: So You Want to Be an Inventor? is similar to the presidents book in that it assumes that you, the kid reader, might be interested someday in inventing something and tells you something about the great inventors.

And I think our book goes beyond other books about inventors in some way. For one thing, it talks about some people you never heard of or you'd never suspect as being inventors. A good example is Hedy Lamarr, the Hollywood movie actress, who actually, in private life, was a genius and who invented a way of interrupting radio wave signals that she thought was going to end the Second World War by wiping out Hitler's subs. It was never used for that purpose at all, but it's used every day now. It's what made the space program possible. And microwave ovens.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What kind of research did you do for Inventor?

DAVID SMALL: My research centered around photographs of inventors and photographs of their inventions. And one of the most helpful things to me was going to Greenfield Village and the Henry Ford Museum, which is just outside of Detroit. I grew up in Detroit and visited the Henry Ford Museum often. So I was familiar with these huge steam engines and locomotives that they have there and the Spirit of St. Louis hanging right over your head, Lindbergh's plane and Edison's workshop.

But having to do this book, I went back there with a fresh eye. What the actual visiting of some of these places and inspection of these objects did for me in this book was to be able to depict them with a kind of hominess. I wanted it to seem as if I was very familiar with these things or as if I had spent some time with Edison and his crew of helpers in his workshop. I wanted that kind of "you-are-there" feeling.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What has been unique for you about the So You Want to Be books?

DAVID SMALL: I've really enjoyed doing the So You Want to Be books, because of the variety of things I've been able to draw, and the variety of ideas and lives expressed. I mean, every time you turn the page, it's a different situation, a different mechanism, a different environment, a different part of the world, a different life being depicted.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You re-illustrated Russell Hoban's The Mouse and His Child.

DAVID SMALL: The Mouse and His Child was a big experience for me. When I was in my twenties, somebody told me that I should read that book. And even though I never read the full book at that time, I remember reading the first couple of chapters and thinking, "Wow, this is amazing. I didn't know things like this could be published for children. This is a book that really tells the truth." And I remember thinking, also, if I ever had anything to do with children's books, it would be nice to either write or illustrate a book like that.

So years later, when Arthur Levine gave me a chance to do it, I felt as if things had come full circle for me in some way. And then, of course, I did read the whole book, several times, and really became very deeply involved with those characters and that situation.

I feel The Mouse and His Child hangs together in a way that most books do not. Russell Hoban was really inspired when he wrote it, and you can feel that all the way through the book. He was really onto something.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What about The Mouse and His Child appealed to you so strongly?

DAVID SMALL: Russell Hoban created a tremendous marriage of characters and philosophy. The plots, the wind-up toy characters, the settings, they all work together to support basically a dark vision that the world is kind of a dump. And we all have to find our ways of surviving in it and of making it a better place. It's a world where we don't have much help, other than what we bring to the table. It's a world in which brotherly love counts more than anything else. I think the book says that maybe we help each other for sometimes selfish motives, but that doesn't matter. What matters is that we work together, that we all do get through it somehow.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do your illustrations bring to The Mouse and His Child?

DAVID SMALL: I brought some of the environments that I knew as a child to the book. I grew up in a rather harsh industrial environment, Detroit, in the forties and fifties. Which wasn't without its dark poetry.

And, wherever you're brought up, that is where your nostalgia lies. And my dreams still are infected by visions of slag heaps and chain-link fences and glowering skies and belching smokestacks. And yet there was life going on there. That's the life that I knew. That's the life that I saw out of the window of the cars that I was riding in. This is what I had in mind as I created the illustrations for The Mouse and His Child.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Describe your typical workday.

DAVID SMALL: I try to be very disciplined. I get up around seven in the morning, and I am at work, here in my studio, by eight-fifteen. I work straight through till lunch. Then, I come back after lunch, and I continue working until six or six-thirty. And then Sarah and I have dinner together. And if I'm really going on a project, I will come back and work 'til midnight or longer, if I have to.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you do when you get stuck?

DAVID SMALL: You have to get through those periods of being blocked. Everybody has them. For me, they have everything to do with self-doubt. It's never a matter of laziness or inability. It's just a matter of believing that what I'm doing is worthwhile, that it matters.

I just make myself work. I just make myself go to work, whether I feel like it or not. And if, for some reason, I cannot bear to work on something that needs to get done, I'm not going to force that. I'll just take a mental vacation. I think the best solution sometimes to working out a problem is to walk squarely away from it.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you tell children when you visit schools?

DAVID SMALL: When I talk with kids, I try to tell them about what it was like to be me as a kid, that is, to be kind of a creative outsider who didn't know his own powers yet. My life was tough as a kid in school. And I think all kids feel that their lives are tough, and that they've, been given an unfair shake for one reason or another. So I think there's a lot of kids who relate to my story. They also relate to the fact that I got out of it. And I tell them that my refuge from all that was books — the library was my safe place. And the art room was my safe place because there I knew what I was doing.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What's do you get out of being children's book author/illustrator?

DAVID SMALL: I'm a great admirer of literature and the power that it has to delve into the human mind and to move through time, which pictures can't really do. So back when I became a children's book author/illustrator, it was a perfect way to combine my two interests.

Also, writing stories, adopting other characters, making up fantastic stories and tales, this is a way of perhaps enhancing who I am. Writing stories takes a commonplace old life and makes it all somehow more interesting. And hopefully I can do that in a way that touches a lot of people in their lives, too.

This In-depth Written Interview was created by TeachingBooks.net for educational purposes and may be copied and distributed solely for these purposes for no charge as long as the copyright information remains on all copies.

Questions regarding this program should be directed to info@teachingbooks.net