In-depth Written Interview

with Louise Erdrich

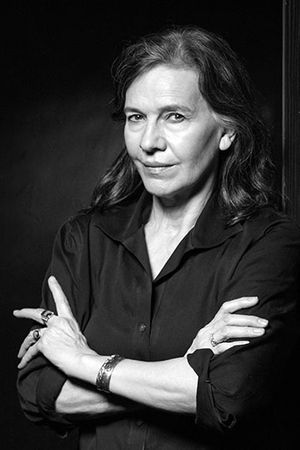

Louise Erdrich interviewed in Minneapolis, Minnesota on October 23, 2009.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You are an award-winning author of books for adults and children, including The Birchbark House, a National Book Award finalist, and The Game of Silence, winner of the Scott O'Dell Award for Historical Fiction. I hope that you get great satisfaction from writing.

LOUISE ERDRICH: I have always enjoyed writing, and it gets better every year. To tell you the truth, I don't know how to do anything else. Sometimes I think if I didn't have writing, I don't know who I would really be. It's the best feeling possible when it's going right. And I feel completely lost when my writing is going poorly.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Were you a writer when you were a child?

LOUISE ERDRICH: When I was about six or seven years old, I remember my father gave me a nickel for a story I wrote. With those five cents, I walked down to the store and bought a grape Popsicle.

I thought this was the best feeling—that I could earn a Popsicle, and I wanted todo it some more. I cannot say I became a writer then, but I remember that my father was very encouraging.

At the same time, my mother liked to make covers for the books that I wrote. She even made covers for books before I knew how to write. I would draw the pictures and tell her what the people in my pictures were saying.

TEACHINGBOOKS: It sounds like your parents were very supportive of your interests.

LOUISE ERDRICH: They are wonderful people, and they're both schoolteachers. They still live in North Dakota where I grew up. They grow a tremendous garden every summer filled with all sorts of berries and every sort of vegetable, and they have a little apple orchard as well. It's not a very big yard; they just use every bit of it.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You're one of seven siblings.

LOUISE ERDRICH: I'm the oldest of seven, and I have to say I don't know that I was a very good oldest sister all the time. I identify with Omakayas, my character in Grandmother's Pigeon, because of how it felt to be an older sister and to have a mixture of feelings about younger siblings.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What inspired you to begin what's going to become your eight-book series—The Birchbark House books?

LOUISE ERDRICH: I wanted to tell the story of where my mother's people had come from. We used to visit Madeline Island frequently—that's where my ancestors lived. I loved being there; it had such resonance for me.

I started writing these books when I was on Madeline Island, Wisconsin, drawing illustrations of stones and crayfish. There are all sorts of little things in the books that are drawn from things that I picked up on the island.

Now I go up to visit Lake of the Woods in Minnesota where the next Birchbark books are set. The books tracing our family tree through a series of generations—showing how they were driven from Madeline Island in Lake Superior, across Minnesota, and up past Lake of the Woods.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Please share more about that history.

LOUISE ERDRICH: My ancestors were driven by the westward expansion of European settlers who wanted more and more and more land. The Ojibwa were driven out onto the plains. Eventually, my great grandparents ended up all the way over in Montana. Then they doubled back and got land in the Turtle Mountains, which are on the plains in the very center of North Dakota up near the Canadian border. I thought this was an incredible familial journey, and I began to write it.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you hope readers take from your Birchbark House series?

LOUISE ERDRICH: Someone has said my series is like the opposite or the other side of the Little House on the Prairie series. Of course, those books everyone reads, including me. When I heard that, I thought, "I didn't start out that way, but I'm awfully glad when people do read The Birchbark House and the rest of the books along with the Little House on the Prairie books, because one of the things about the Laura Ingalls Wilder books that always distresses me is Ma's racism. She's a terrible racist about native people."

And there's also inherent racism in the structure of the Wilder books themselves: the simple acceptance of the fact that the Little House characters could just go along and take whatever they wanted and that the native people were apparently vanishing into the sunset. The natives were portrayed as vanishing people who were going to go away. And that's all that one could feel about them.

But what was really happening was the native people who were being pushed out of the regions that were being settled had been disposed of their land through a very painful means. Someone in the tribe had usually signed treaties, but they hadn't wanted to. They'd want to just stay where they were. But they were forced to sign treaty after treaty with the U.S. government.

In time the native people were either going to be concentrated on smaller and smaller pieces of land, or they had to move ahead of the settlers. And that piece of American history is glossed over. It's never told the way it really happened.

The native people are always looked at as always the same kind of people: they have a couple of feathers sticking up, and they seem strange and foreign. They're always imagined as being way back in the past, and they don't have families.

Readers don't know that native peoples had a warm family structure to their lives. And readers don't know that native people had and still have great senses of humor and that there's this humanity that's been lost in the public perception about Native American people.

In writing the Birchbark books, I wanted to make the books very accessible. I want people to enter into this world, and children especially to identify and enter into a world where they are among a Native American family. This family had its angers, trials, happiness, pains, heroism, desperation, and annoyances. You know, everything that anyone's family has.

I want readers to have a more complicated grasp of Native American people and realize that people have survived. People to this very day are speaking their language and living in their own culture and have a tremendous variety in their cultures. That's what I wanted to do with these books.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You mentioned a contrast to the Little House on the Prairie books. Are there similarities that you believe in?

LOUISE ERDRICH: One of the things that I always liked about the Little House on the Prairie books was the specificity of everything that the family made or used. Readers have so many images from those books, like how sausages were made, for example. And Ma was always stuffing mattresses with hay. Children were eating pork cracklings, wearing handmade clothing, and using handmade soap.

When I began The Birchbark House, I wanted to have this level of detail, too. So, I try to actually experience or do in real life almost anything that my characters do in my books. I can't really hunt bears, but I try to do some of the other things that my characters do in the books.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Is that the way you do research?

LOUISE ERDRICH: It's not research. It's just life. It's just the way the drawings come out of photographs or the way I place an object into a story. There's a chapter called "Hunger," and it includes a little makak—a birchbark eating bowl. I had that bowl, so I drew it. I try to draw and do things from life and draw things from life just the way my characters would.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You illustrate the Birchbark House books beautifully. Do you consider yourself a fine artist as well as a writer?

LOUISE ERDRICH: My mother liked to sit down with her children and draw with them. She was always wonderful about that. She taught us how to sew, how to can, how to make books, how to grow any sort of plant, and how to draw. It was just part of what she taught us.

I just grew up thinking I was able to draw, even though I couldn't. I took some art classes when I went to college, but I never really learned what drawing is.

When I started working on these books, I thought I would get a real artist to make the drawings for them. But the problem was that so many things in the books had to be drawn from life or from real objects. They were so specifically Ojibwa that I decided that Ihad to do it myself.

So almost everything that's in the books is taken from around my house, or it's drawn from photographs of my own children (I have four daughters and plenty of lively nephews). So they're very personal drawings. If it's in the book, I probably have drawn it from something that I can see with my own eyes.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What's an example of something you had around the house that you drew in The Birchbark House?

LOUISE ERDRICH: In The Birchbark House there's a crow named Andeg, which is the word for crow in the Ojibwa language. I drew this crow from life, because we raised a pet crow. The crow had fallen from his or her nest (we never knew if our crow as a male or female). I became very fond of the crow. It was one of the dearest pets that we ever had. On the hardcover version of The Birchbark House, my author photo shows me with our crow on my head.

The crow used to sit with me while I wrote, so we became very close friends, and I was able to write about and draw the crow for the book.

We didn't really know quite how to raise a crow. So, we called a lot of people to find out. It's actually not something anybody should do anymore, but this was years ago. We managed to feed this crow by pretending I was its parent. I looked at how crows fed their children and I took a little bit of hamburger, and I feed it on the end of a rubber eraser pencil. You have to be very crow-like when you adopt a crow.

But as I say, nobody should do this. It is best to send injured birds to a wildlife rehabilitation center.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Your connections to animal life and nature are multileveled.

LOUISE ERDRICH: I have to have animals around me in order to feel that I'm living on earth. At one time when we had lots and lots of pets around our house: a rabbit, flying squirrels, dogs, guinea pigs, rats, iguanas ... Anything you could buy in a pet store, we've probably had it at our house—except a tarantula.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Why, as a parent, do you want your own to experience living with so many animals?

LOUISE ERDRICH: I think it's very important to realize that we're not the only species onthe earth. And at a very young age, at least one of my daughters became a vegetarian. Two of my sisters and their families are vegetarians. I'm a vegetarian. Another daughter is a vegetarian. Slowly, the whole family is being converted to vegetarianism. And I think it's partly because of this close connection with the animals that live around us. We have an instantaneous connection to animals. We are curious about them as other forms of life. We don't think about them in terms of intelligence. We assume that they have a different sort of intelligence.

I could see this understanding in my children, that they assumed that all insects had equal intelligence and feelings and that everything around them had some sort of intelligent life or spirit within it. There is a certain truth to this. But we lose this understanding as we grow older. I had the same thing happen with my children. They simply wanted to have animals around them. And, I had parents who allowed me to have animals around me.

My father brought home a baby raccoon for me when I was a little girl. I wouldn't suggest anyone having a baby raccoon, but this was one of the most delightful creatures in the world and a wonderful baby pet. I was able to raise it until it got old enough to wander away and live on its own. I had every kind of lizard, chameleon, anything you could find in a comic book.

TEACHINGBOOKS:No pet rocks?

LOUISE ERDRICH: Yes, we have a pet rock. But here's the interesting thing: In the Ojibwa language we don't assign male or female to objects (like in Spanish). Objects in Ojibwa are either animate or inanimate. And a stone is animate.

So if you think about it, many people think of stones as just lumps of something lying there. But we have no idea where a stone has been. We have no idea how it's come to be where it's sitting. We don't know at all anything about this. That's why it's animate.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What are some examples of inanimate objects in the Ojibwa language?

LOUISE ERDRICH: Something like meat would be dead. So an inanimate would be something that had to do with the spirit world. A lot of things that were brought in by Europeans weren't perceived to have this sort of animation. Things that are made are not animate. But oddly, there are also things that you would think would be animate but they're inanimate, like water.

There are long stories that go with every word. And every word in Ojibwa has a spirit that goes with it and a history that goes to it. Just like the English language has a very long history.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How did you come to know so much about your Ojibwa heritage? Did your parents teach you? Did you hear a lot of these stories from them?

LOUISE ERDRICH: Oh, no. I've made it my life study to try and learn as much as I can. I don't know any more than a three year old knows, really, in a traditional sense.

I remember my grandfather and my mother taught me a great deal about what it is to be an Ojibwa person just by the way they were. I grew up in a very small town environment with large number of native people around me, because my parents worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

I was taught by German nuns, so I spoke a lot of German as a child. I learned German as my other language. I have a very mixed background, and I feel there's a huge paucity of knowledge in my life about the Ojibwa language and culture. So, I keep trying to add to it.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Is this part of why you write, to have a place for this exploration?

LOUISE ERDRICH: No, I would write no matter what. This has become clear to me: I don't really have a choice. I have to write. I don't enjoy any other activity as much as I enjoy writing. I love telling stories, and I love being immersed in a book. I get enormous happiness and satisfaction from telling the story the way I feel I ought to tell it.

I've also written about the German side of my family. I don't think I've exhausted all of what I'd like to write, and I feel I'm just beginning to write about Ojibwa people and culture.

For example, in The Birchbark House, I used a name that was on a very old tribal roll, and it was Omakayas. But the real true way to say "little frog" in Ojibwa is "Omakakeens." Either there was a dialect that had been lost where Omakayas would be the way to say little frog, or the person who was non-Ojibwa speaking who wrote the name down wrong. I don't know which. But I still wanted to use that old spelling in the book.

TEACHINGBOOKS: There are two types of stories within your Birchbark House books: the story itself, and then the storytelling within the main story—stories told by characters in the books.

LOUISE ERDRICH: I wanted to include traditional stories and storytelling in the book. I wanted to tell a narrative of the people's lives but also make the storytelling part of the narrative so that the readers would know that this is how people entertained themselves—they told these stories.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Do you do that in your own life? Do you tell stories as a family?

LOUISE ERDRICH: I tell my children stories, and we often make our daily life into a story. My parents were terrific storytellers, so we did this when I was a child as well.

However, I didn't learn traditional stories—I learned that everything was a story and that anything that happened during the day was potentially a story. That's what comes with talking a lot, hearing your parents talk a lot, and having an extended family who talks.

That's also something that happened to me. We had a television, but we weren't really allowed to watch it except when something special was on. So I was really raised without watching television compared to the amount people watch it today. The first thing I remember watching was the Shakespeare's Age of Kings on PBS. There was this wonderful production of Henry the Fifth and the other history plays. We were able to watch that with my dad.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Please share what it was like to write your picture books. Jim Lamarche's illustrations in your picture book, Grandmother's Pigeon, were extraordinary.

LOUISE ERDRICH: I agree. I can't imagine a better evocation of what that book was all about. The interesting thing about Grandmother's Pigeon and the illustration was that he imagined objects and things that I actually had in my house. He drew a desk with all sorts of things around it, and when I first looked at the drawings I was astonished, because he'd actually included the sorts of things that I have around my desk. He's very intuitive. He's a wonderful, wonderful artist.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You write about the natural world in such a way that readers learn so much. Through your books, they are able to experience a connection to the natural world.

LOUISE ERDRICH: My mother and father are great gardeners. They're also hunters and gatherers. I used to go out with my father deer hunting every fall. I would go out with him and sit in our tree and try to shoot a deer, but the real point of going out was to be in the woods and to gather. We had gathering sacks, and we'd come back with wild plums, asparagus roots to plant in the yard, and lots of wild mushrooms.

In Minneapolis, where I live, the city is decorated with high bush cranberries as ornamental plantings. But for Ojibwa people, these plants are a wonderful source of allsorts of vitamins: they make a great jam, and they are a great seasoning for food. I still go and harvest buckets of high bush cranberries from the park in Minneapolis.

My sisters and I have edible yards; we plant things, and we eat them. It's pretty simple. The natural world is just a part of who I am; a part of my life.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Can you share an example of how your connection to the natural world comes through in your books?

LOUISE ERDRICH: A puffball is a type of mushroom—a fungus. The little ones that grow in the woods are round, and when they are all dried up in the fall, they burst open and their spores go everywhere and then reseed themselves.

As a little girl, I liked to go around and just pop the puffballs open, because this dust comes out of them. That dust is ganebig medicine. It's snake medicine that is very good for putting on cuts and wounds.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Please talk about the sequential story you have written with The Birchbark House, The Game of Silence, and The Porcupine Year.

LOUISE ERDRICH: In the Birchbark books, I'm trying to retrace the forced migration that my family and my ancestors experienced. It was a migration that my ancestors underwent. They begin at Madeline Island in Wisconsin, and they end up in the Turtle Mountains in North Dakota. The books are going to cover span of a hundred years.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What would you like to share about your writing of the first in this series, The Birchbark House?

LOUISE ERDRICH: The Birchbark House began as a story that I told my daughters. I told them about this girl who had been left alone on an island and how she survived and about how she was rescued by an old woman.

As I began to do research, I found a depiction of this woman who actually did hunt for bear with a spear and who was an Ojibwa woman. She was well over six feet tall. She had a tattered and dramatic looking coat that she wore. And she had a pack of dogs.

I had this experience in the writing of the book that was very peculiar. I would be drawn into research, but I would find in the research a corroboration of what I'd already written. So I would keep going back and forth between research and the present and the past. It all came together for me in a wonderful way.

TEACHINGBOOKS: The next book in the series is The Game of Silence.

LOUISE ERDRICH: I always loved this game that I played with my children. It is an old Ojibwa game that I think a lot of people play to this day. It's a cross-cultural parent's way of keeping your children quiet wherever you're going. You play how long can you stay quiet? And the one who wins gets a prize.

I used to play it with them when I needed them to be really quiet. When Ojibwa parents needed to discuss something serious, they would put out a pile of gifts and the children would be able to choose from them as long as they maintained perfect silence while the adults discussed the business they had to attend to. This is something they had to evolve during long winters in the small quarters of their birchbark lodges.

I thought this was a great title and a great game. I also wanted to use the game and its name, which has a certain menace to it, to describe how my little family was going to have to move on into a world where they would be more threatened as they left their home on the island.

TEACHINGBOOKS: The Porcupine Year is the third book in your series.

LOUISE ERDRICH: Yes. The books portray a generational cycle, and with each of the books, I use a different child narrator.

I use information from trappers-' journals, history books, oral history, and other historical sources. There is an oral history that recounts rescuing settlers' children. I was told about this by an Ojibwa elder, who shared that the children had been adopted and lived with an Ojibwa family for some time. So, I used that story within The Porcupine Year.

I also use a different animal in each book. I was really astonished when I found out that a friend of mine, a quill maker, had kept a porcupine as her pet for many years. I've always had a special feeling for porcupines, so I wanted to use one as a character in one of the books.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Your book Tracks, is used in high schools.

LOUISE ERDRICH: Tracks, is about land loss. During the years that it was written, an enormous amount of land passed, again, out of Native American possession because of something called the Allotment Act.

Tracks, is often studied along with the Allotment Act and the Dawes Act, because it really reveals how even after Native American people had given up all their land, except for a few scraps, it was nibbled at and eaten away at by acts of Congress and by the state that each tribe was in. People keep buying it from desperate native people.

Tracks, is a book about continued dispossession, and about the affect Catholicism has on native people. It also shows how funny people can be. I hope one thing that comes across in each of my books is that native people really are some of the funniest people. Relaxing with any group of native people, you're just laughing most of the time. Everybody's just very funny. Anyone who gets to know native people immediately begins to realize that he or she is in a joking culture.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Please describe a typical workday.

LOUISE ERDRICH: I bring my youngest daughter to school. Then I come back and drink tea. I walk around the lakes here in Minneapolis with my dog and sometimes with a friend or with my husband, and (if I'm alone) I think about what I'm going to do. Then I go upstairs.

I have a special red chair that I have sat in ever since I started writing. So, I sit down in my chair that is stuffed with old, tired-out sentences. And, it's my "sentence" to sit in that chair until I stop writing, which will never happen until I'm gone. It's my chair. I work as long as I can.

I write by hand. My earliest writings were written in children's tablets, and myhand writing is all faded now. After I handwrite, I then put my work onto the computer. My computer is one of those old Jetson computers, and I only use it for word processing.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you do when you get stuck?

LOUISE ERDRICH: When I get stuck, I try to make myself go out and walk more. That's when I go into the woods. Fortunately, I'm close enough so that I can walk into some fairly dense woods, even here in Minneapolis. If I'm really stuck and nothing's going well, I drink a lot of coffee.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you like to tell students?

LOUISE ERDRICH: I like to tell them that whatever they do in life they should persist in it. They should decide what it is they want to do, and consider what makes them happiest—not what everyone else wants them to do. Choose something that makes them happy. Feel good and happy. And then don't stop doing it, no matter what anyone tells you. That can be one's life's work.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you like to tell educators?

LOUISE ERDRICH: I like to tell them about my father and my mother, and how they really never stopped teaching. That everything to them is a natural idea for teaching.

I like to say that I am sorry that if you're not teaching at a private school that you have so much paperwork to do. I think paperwork is a great burden. I have children in public school, and I've had children in private schools. In public schools, I think it's very difficult to teach in a natural way. Teachers have to be so careful to make certain that they have completed forms that fill enormous drawers. I tell teachers I hope that they persist and that all of the paperwork they have to do does not destroy their natural love of teaching and their love of being with young people.

I also tell teachers and librarians not to give up their strongest instincts about books. I think right now we're facing a very interesting time and we're perhaps looking at a time when people are more in love with the screen than with the printed word.

I hope people don't give up on the printed word. I think that books are a wonderful form of technology, and I hope that we can keep reading them in any sort of way.

This In-depth Written Interview was created by TeachingBooks.net for educational purposes and may be copied and distributed solely for these purposes for no charge as long as the copyright information remains on all copies.

Questions regarding this program should be directed to info@teachingbooks.net