Audiobook Excerpt narrated by Emily Rankin

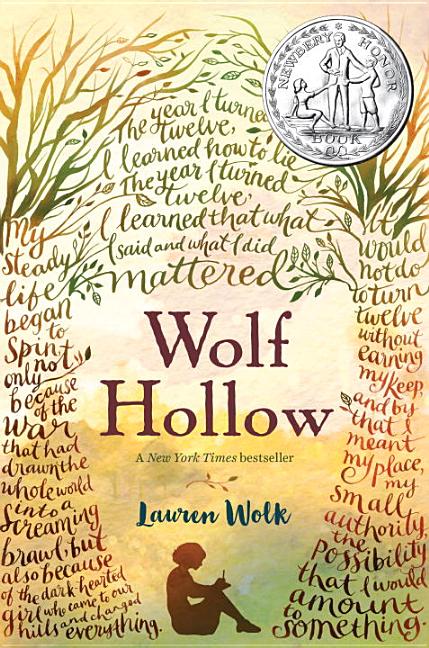

Wolf Hollow |

Audiobook excerpt narrated by Emily Rankin.

Volume 90%

Press shift question mark to access a list of keyboard shortcuts

Keyboard Shortcuts

Play/PauseSPACE

Increase Volume↑

Decrease Volume↓

Seek Forward→

Seek Backward←

Captions On/Offc

Fullscreen/Exit Fullscreenf

Mute/Unmutem

Seek %0-9

Translate this transcript in the header View this transcript Dark mode on/off

This audio excerpt is provided by Books On Tape® / Listening Library.