Audiobook Excerpt narrated by Karen Chilton

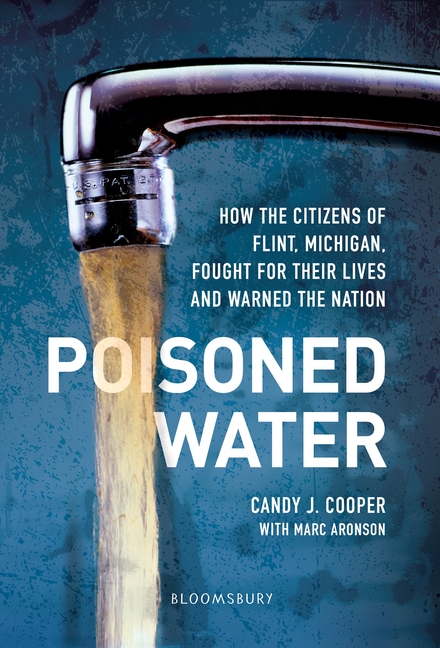

Poisoned Water: How the Citizens of Flint, Michigan, Fought for Their Lives and Warned the Nation |

Audiobook excerpt narrated by Karen Chilton.

Translate this transcript in the header View this transcript Dark mode on/off

Chilton, Karen: Voices rise out of a console telephone on the table. I am there to describe the book I am hoping to write and to ask for the group's help. I am a native of Michigan and have worked and studied in the state, but I am aware of my Flint outsider status. The room is very quiet. The woman to my left, Elder Bailey, is a lifelong Flint resident, a church pastor, a community health advocate and an expert on acute care for stroke victims. I have heard her speak on a panel about the underlying social determinants of the water crisis. Where she described the water's effects on her family, her friends, and her own health after she spent eight days in intensive care with a severe cough. Today, she wears a jacket, her hair upswept in neat cornrows. I am aware that race is the elephant in the room, as De'Loni has often said.

She says it's in the water crisis room and in the room of America. I know that Flint is highly segregated by race and income level. I am white, and Bailey, Evans and De'Loni are black. But I also know that water harmed everyone in Flint, not just one group or one house or one neighborhood. It harmed people who worked in Flint and lived outside of Flint. And the crisis inspired a commingling of racial, ethnic, religious, and income groups working together. Flint has a very strong community spiritedness that arises, especially in moments of struggle. Most famously, during the brutal Flint sit-down strike of 1936 to 1937, which led to the consolidation of the United Automobile Workers, the unionization of the US automobile industry and the conditions that would help build the American middle-class during the coming years.

And now I listen as Elder Bailey begins to speak with a grave authority, as if uttering difficult truths for an entire community. "You have got to understand that we have gone through trauma," asserts Bailey with a furrowed brow. "Trauma upon trauma upon trauma," she is emphatic. "The water crisis didn't begin in 2014," she continues. "The water crisis began long before that, years before that. It's been a long time." She was talking about a Michigan law first passed in 2011, that had allowed the state to take over Flint after the city slid into massive debt. The governor appointed a single person to run Flint, an emergency manager. The first was Michael Brown. Three more men would serve in sequence after Brown, each imposing a starvation diet of austerity.

Flint's elected council and mayor were disenfranchised, denied the right to vote. Citizens could no longer decide what to cut or what to save. The mayor became a figurehead, no longer in charge of anything. All decisions fell to the debt slayer, the emergency manager. Elder Bailey was referring to recent history, but there is a deep pool of injustice in Flint's overall history as well. Flint was built on car manufacturing, the expansion of General Motors. And it is hard to overstate the winning all American spirit of the town at its peak, at least from the outside. Flint had been a model city with excellent schools and a solid middle-class standard of living.

Elder Bailey and others in this conversation had lived in Flint then. "We've seen it in flourishing times," Bailey says. "We were an awesome community. We were above average in a lot of things. We were a model community for many, many years." Flint was also a leading American example of ignorance, extreme racial segregation and economic polarization. It's as if every major social conflict in American history criss-crossed in Flint. "The city acted as the canary in our country's conscience," wrote one Flint resident, Ted Nelson, in an essay about his move from Los Angeles to his now ...

This audio excerpt is provided by Recorded Books.